Chetty's Charts

Harvard economist Raj Chetty vindicates Donald Trump's sense of the white working class getting cheated out of their patrimony.

Harvard economist Raj Chetty has released a new paper based on a colossal 57 million people born between 1978 and 1992. Chetty has managed to get his claws upon their parents’ 1040 tax forms from 1978-2019 and their own 1040s up through 2019.

Chetty’s conclusion is that working class whites have indeed been getting the fuzzy end of the lollipop, just like Donald Trump and Angus Deaton have been saying:

… VII Conclusion

This paper has shown that economic outcomes deteriorated sharply for white children from low-income families in recent birth cohorts in the United States, while improving for white children from high-income families and Black children from across the parental income distribution. These divergent trends in economic mobility were almost entirely driven by differential changes in the social environments in which children grew up by race and class. In particular, outcomes improve across cohorts for children who grow up in communities with increasing parental employment rates, with larger effects for children who moved to such communities at younger ages. Children’s outcomes are more strongly related to the parental employment rates of peers they are more likely to interact with, suggesting that social interactions mediate changes in economic mobility….

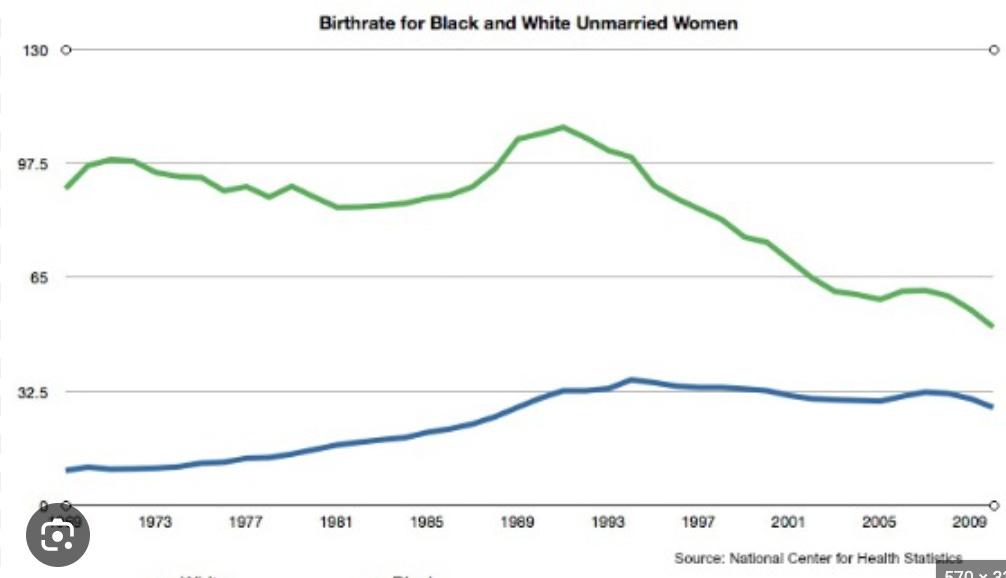

A big part of what is going on is that fertility was much higher among lower class blacks than higher class blacks up through 1991, after which fertility among black teen mothers dropped sharply. Chetty’s database consists of people born in 1978-1992, so while he finds both lower and higher class blacks to be getting better off, there was a sizable dysgenic/dyscultural effect in 1978-1992 making more births to lower class blacks.

Blacks haven’t been talking like they’ve been doing well lately.

Higher class blacks aren’t catching up with higher class whites. Lower class blacks are catching up with lower class whites, but some of that is due to whites falling down.

Chetty’s 2024 paper

… Between the 1978 and 1992 birth cohorts, household incomes in adulthood fell sharply for white children growing up in low-income families. At the same time, incomes increased for white children growing up in high-income families. These divergent trends resulted in growing white class gaps, with the intergenerational persistence of household income ranks for white children increasing by 28%. The gap in average household incomes for white children raised in low-income (25th percentile) versus high-income (75th percentile) families grew from $17,720 in the 1978 birth cohort to $20,950 in the 1992 birth cohort. In contrast, incomes in adulthood increased across all parental income levels for Black children. As a result of these trends, white-Black race gaps for low-income families shrank: the gap in average household incomes between white and Black children raised in low-income families fell by 28%, from $20,810 for children born in 1978 to $14,910 for children born in 1992. The class gap among Black families and the white-Black gap among high-income families remained essentially unchanged. Intergenerational mobility also changed much more modestly for Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian children during the period we study.3

The white-Black race gap among low-income families narrowed primarily because of changes in children’s chances of escaping poverty rather than their chances of reaching the upper class. In the 1978 cohort, Black children from families in the bottom income quintile were 14.7 percentage points more likely to remain in the bottom quintile than their white counterparts. By the 1992 cohort, this gap shrank to 4.1 percentage points—a 72%reduction in the racial gap in the intergenerational persistence of poverty—a measure that has been the focus of recent policy discussions (National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2024). By contrast, there was relatively little change across cohorts in the likelihood that white or Black children from families in the bottom income quintile reached the top quintile of the income distribution.

We find similar patterns of growing white class gaps and shrinking white-Black race gaps for early-life outcomes, including educational attainment and SAT and ACT scores. These results show that outcomes began to diverge even before children entered the labor market. Non-monetary outcomes, such as marriage, incarceration, and mortality rates also exhibit similar trends, indicating that the changes extended well beyond economic outcomes. For example, the white class gap in early adulthood mortality more than doubled between the 1978 and 1992 birth cohorts, while the white-Black race gap in early adulthood mortality decreased by 77%.

Outcomes deteriorated for low-income white families and improved for low-income Black families in nearly every part of the country, but the magnitudes of these changes varied across areas. Economic mobility fell the most for low-income white families in the Great Plains and the coasts, areas that had enjoyed relatively high rates of mobility in the 1978 birth cohort. By the 1992 cohort, these areas had levels of economic mobility comparable to the Southeast and industrial Midwest (e.g., Ohio and Michigan), which had low levels of mobility for all cohorts in our data. Economic mobility for low-income Black families increased sharply in the Southeast and the industrial Midwest, with modest changes on the coasts. Despite these divergent trends, low-income Black families still had significantly lower levels of economic mobility than low-income white families in virtually every county even in the 1992 birth cohort because the initial white-Black race gaps in mobility were so large for the 1978 birth cohort.

Trends differed even among cities with similar demographic characteristics and economic trajectories. For example, Charlotte, NC and Atlanta, GA—two rapidly growing cities in the Southeast with similar demographics—both had very low rates of economic mobility for children born in 1978, particularly for low-income Black families. Economic mobility for Black families increased sharply in Charlotte, reaching the national average for low-income Black children in the 1992 birth cohort, but remained low in Atlanta.

OK, that’s just because the Carolinas got absolutely hammered by 2008 because Charlotte’s economy was so dependent on things like mortgage lending (Wachovia), lumber, furniture, home-building, and golf, so residents took a beating when Chetty measured there income in 2010-11. But by 2019, Charlotte was back in good shape.

A general problem with Chetty’s research project of finding the places in the country with the most opportunity-promoting policies is that Chetty can reliably be distinguish long-term wise policies from shorter-term localized booms and busts. Thus, Charlotte was the Big Bad Example in his 2013-2015 papers, but now it seems pretty okay. Likewise, North Dakota was the promised land in his earlier papers because of the fracking boom, but that has faded.

… We start by showing that changes in family characteristics, such as parental education, wealth, occupation, or marital status, explain only 7% of the growing white class gaps and 10% of the shrinking white-Black race gaps. We then show that the differential trends persist even when we control for childhood Census tract-by-cohort fixed effects, implying that white class gaps grew and white-Black race gaps shrank even among children who grew up in the same Census tract. The divergence in economic mobility must therefore be driven by factors that impact race and class groups differently within a given neighborhood. …

For example, the outcomes of white children with low-income parents deteriorated much more sharply in areas where employment rates for low-income white parents fell more.

For example, if lower income white parents tended to have union jobs down at the Plant, but then the Plant moved to China, the parents are going to lose their jobs and their kids aren’t going to have the opportunity to get union jobs at the Plant.

… As a result, the growth in the white class gap and the reduction in the white-Black race gap can be explained almost entirely by the sharp fall in employment rates for low-income white parents relative to low-income Black and high-income white parents over the period we study.

… Similarly, for Black children growing up in low income families, the employment rates of low-income Black parents are generally far more predictive of outcomes than the employment rates of low-income white parents. Counties with greater interaction across racial lines are an exception to this pattern. When Black children constitute a small share of a county’s population, they are more likely to interact with white peers (Blau, 1977; Currarini, Jackson and Pin, 2009; Cheng and Xie, 2013). In such counties, the outcomes of Black children are related to the employment rates of low-income white parents.

One of the Chetty’s most practical pieces of advice, but one he can’t spell out explicitly for fear of being cancelled, is directed to mothers with black sons: get the hell out of the ‘hood now, move to some white exurb far from your nephews so they can’t recruit your sons into their street gang. If you only have black daughters, the need to leave is less pressing; but getting your sons aways from no-good cousins before they become adolescents and want to join their cousins’ gangs is a no-brainer to save them from becoming career criminals.

The outcomes of Black children are also related to the employment rates of low-income white parents in counties with higher rates of interracial marriage, a proxy for cross-racial interaction, controlling for racial shares at the Census tract level.

E.g., blacks do well in race-mixing Hawaii, in part because so many blacks in Hawaii got their through the military, which doesn’t let in bottom-of-the-barrel recruits, and sees a lot of mixed race marriages, as do Hawaiian civilians. Likewise, the San Fernando Valley is a good (but expensive) place to raise black male youths because there are no black neighborhoods and no black street gangs, just 60,000 mostly middle class blacks who get along fine with other races.

These findings provide further support for social interaction mechanisms, as captured, for example, by the Borjas (1992) model of “ethnic capital” in intergenerational mobility.10 Combining these results, we conclude that a parsimonious theory—that children’s outcomes mimic those of the parents in their social communities—explains the divergent trends in economic mobility by race and class in the United States in recent decades.

… There has also been little change in the white-Black income gap in percentile ranks when pooling parental income groups (Bayer and Charles, 2018). We show that disaggregating the data by race and parental income—which was infeasible with the data used in prior work—reveals divergent trends at the intersection of race and class. These trends were not evident in past work because the improving outcomes among high-income white families were offset by the deteriorating outcomes among low-income white families, leaving the unconditional white-Black race gap relatively unchanged.

I suspect an important factor Chetty is overlooking is that a reason nobody noticed how much better blacks were doing among those born in 1992 than those born in 1978 when decomposed into families below the national median income and families above the national median income was that fertility was much higher (and faster) among 16 year old black single mothers in the bottom half of society than among 37 year old black government workers with master’s degrees. So, while both the bottom half was doing pretty well relative to the white bottom half in catching up on income, the growth of the numbers of blacks raised in the bottom half was growing much faster than the number of blacks raised in the top half.

(Plus, the huge influx of Latino immigrants into the bottom half makes it even more confusing to figure out what is going on.)

… As another example, Grand Rapids, MI and Milwaukee, WI—two Rust Belt cities—both had rates of economic mobility around the national average for children born to low-income white families in 1978. By 1992, however, mobility in Milwaukee fell sharply for children born to low-income white families, while mobility in Grand Rapids rose above the national average for these children.

Get the hell out of urban Milwaukee, especially if you are lower class and white. Who is left of LaVerne’s and Shirley’s descendants born there in 1978 to 1992? Only Squiggy’s progeny, I’d bet.

White children born in 1978-1992 grew up in households with much higher incomes ($91,800 in current inflation-adjusted dollars) than black children ($38,250), in part because 80% of white children were raised in two-parent families compared to 29% of black children.

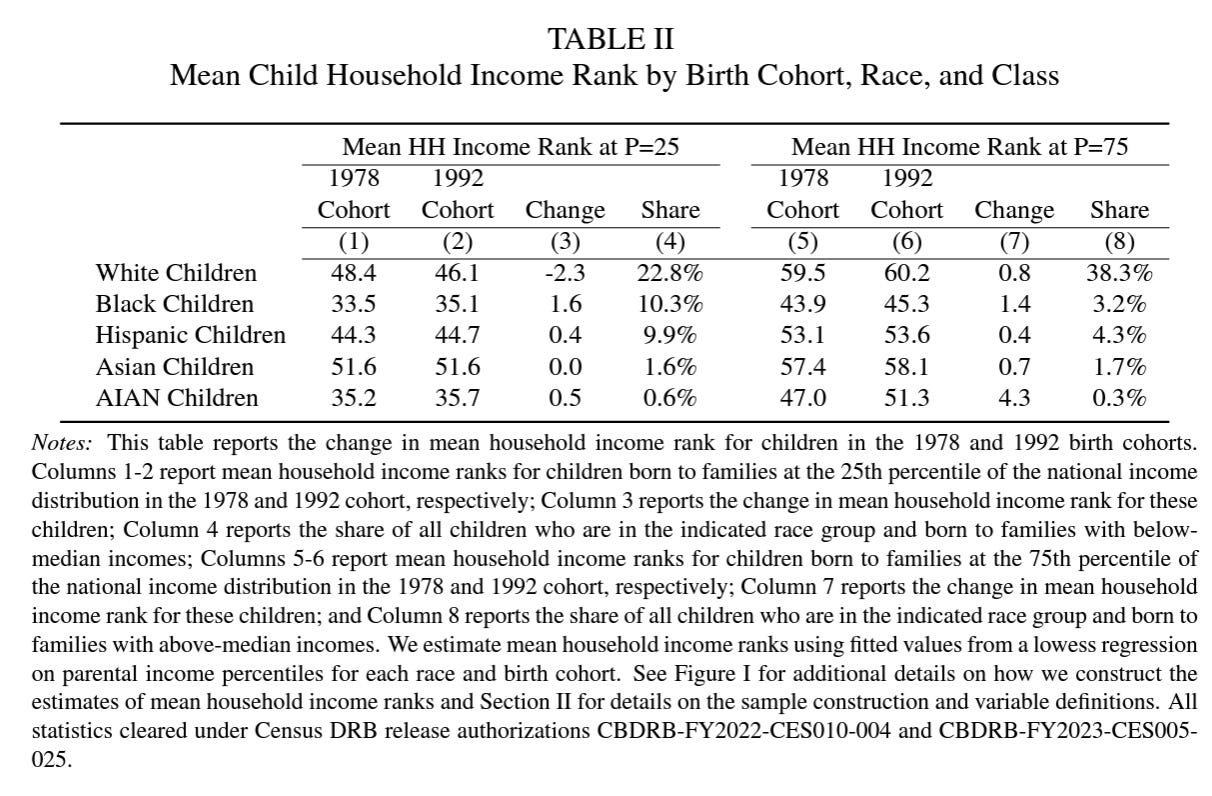

Working class white children born in 1978 and raised in families at the 25th percentile of household income by age 27 had household incomes at the 48.4th percentile in 2005 (some of this is regression to the mean, some of it is increasing diversity, such as Hispanic immigration and black population growth lifting the white working class up the percentile ranks, not because they are catching up with the upper middle class, but because their rank is being inflated by all the very poor people arriving from Gautelombia). Working class white children born in 1992 and raised at the 25th percentile were down to the 46.1st percentile of household income by age 27 in 2019.

In contrast, upper middle class children raised at the 75th percentile by age 27 had improved from 59.5th percentile in 2005 to 60.2nd percentile in 2019.

On the other hand, note that 62.7% of white kids were raised in the top half of household income distribution compared to just 23.7% of black kids.

This is averaging across all births from 1978-1992: Chetty’s chart doesn’t break out whether these trends were changing from 1978 to 1992 cohorts, even though that’s obviously important.

My assumption is that black fertility rates were very high among single mothers through the early 1990s, then dropped sharply. (Graph is by Ta-Nehisi Coates.) The Crack Years around 1990 seemed to see a lot of Births of Exuberance among young black women, just as they saw a lot of Deaths of Exuberance among young black men (see countless gangsta rap hits for details).

Births to black teen welfare mothers are way down since the end of Chetty’s data collection period in 1992, which, to be frank, seems like a good thing, although admitting that will probably get me denounced as a eugenicist/euculturalist.

American elites have substantially reduced the race gap among the working class, in part by increasing the class gap among whites:

Only 3.0% of blacks born in 1978 who were raised in the bottom 20% of household income had ascended to the top 20% of household income by age 27. Fourteen years later, among blacks born in 1992, the exact same 3.0% had ascended to the top quintile of income.

On the other hand, the American Establishment had succeeded in lowering the percentage of obnoxious whites raised in the bottom quintile who had ascended to the top quintile from 13.7% among those born in 1978 to only 3.0% among those born in 1992, cutting the number of non-genteel high income white nouveau riche by well over 75%.

Heckuva job, Establishmenties!

Heckuva job at destroying California as the promised land for Okies! John Steinbeck would be so proud.

On the other hand, I’m dubious of Chetty’s implicit assumption that the 25th overall percentile among those born in 1992 was much the same as the 25th percentile overall of those born in 1978. In reality, at least in giant California, the 1986 illegal immigrant amnesty legislation set off a huge baby boom among Mexican-born Hispanic women in 1988-1995. That would mean that whites born in 1992 were even more significantly downscale objectively than whites born in 1978, even if their fall in living standards was statistically cushioned by the huge surge of illegal immigrants and anchor baby births to Latino families living in garages after the 1986 amnesty.

In general, Chetty is highly leery of dwelling upon the effects of immigrants, such as himself.

Chetty’s excuse is that he can’t figure out how many “unauthorized” immigrants there were in the country, so that justifies him in ignoring their effect.

When I lived in the Bay Area I was in a band with three guys who grew up together, working class, in San Jose. These were GenX guys, a little older than the 1978 cohort. From listening to them chat I got the impression that they were about the only people from their peer group whose lives weren't messed up. Everyone else they grew up with succumbed to methamphetamine. In fact, now that I think about it, the bass player was only recently clean, and I think the drummer kind of bullied him into playing with us to help him with that. One day the drummer had to miss practice because he was going to the funeral of an old friend of his who had clearly committed "suicide by cop".

The guitar player was approximately the last white union carpenter in the region. He told me the bosses would have posters up in their offices that said 'it takes three white men to do the work of one Mexican' (I don't remember if it was three, but you get the point). He was married to a Mexican woman and had one child.

Guitar player's father was also a union carpenter and owned his house in San Jose.

Whose idea were the standards of 25/75% but quintiles of income? Does he ever rank income for a birth cohort separately, or is it always against all incomes of all adults (I assume that's what he's doing)?

The cost of living varies so widely across the country that someone should be measuring how it has changed, too. I suspect that high incomes increasingly congregate where high (and rising) costs are, so who is actually just treading water, not floating famously?