If race doesn't exist, what about species?

Scientists now say the famous snail darter endangered species wasn't a species.

Remember the famous snail darter, the two-inch long minnow that turned the Endangered Species Act from a nice gesture to save some charismatic megafauna like the bald eagle into a juggernaut of NIMBYism?

Well, according to a new study by scientists, it’s never been a species. It’s just a a subpopulation, a race as it were, of the never endangered stargazing darter.

This is of interest both for what it says about the Endangered Species Act and about the current dogma that race doesn’t exist scientifically.

If scientists argue over questions of species all the time, is it surprising that racial categories within the human species aren’t always clear-cut?

From the New York Times science section:

This Tiny Fish’s Mistaken Identity Halted a Dam’s Construction

Scientists say the snail darter, whose endangered species status delayed the building of a dam in Tennessee in the 1970s, is a genetic match of a different fish.

By Jason Nark

Updated Jan. 4, 2025

For such a tiny fish, the snail darter has haunted Tennessee. It was the endangered species that swam its way to the Supreme Court in a vitriolic battle during the 1970s that temporarily blocked the construction of a dam.

On Friday, a team of researchers argued that the fish was a phantom all along.

“There is, technically, no snail darter,” said Thomas Near, curator of ichthyology at the Yale Peabody Museum.

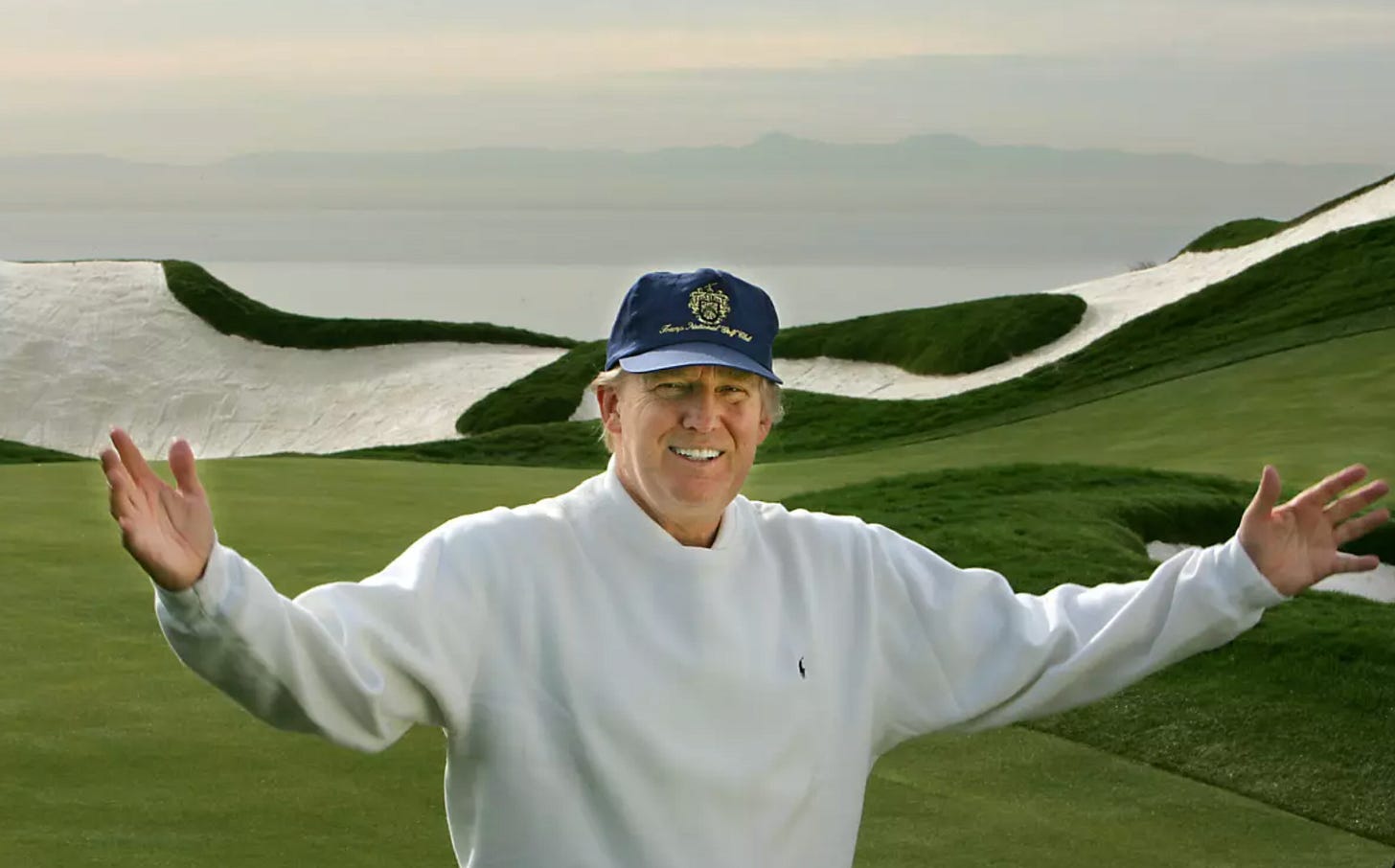

Dr. Near, also a professor who leads a fish biology lab at Yale, and his colleagues report in the journal Current Biology that the snail darter, Percina tanasi, is neither a distinct species nor a subspecies. Rather, it is an eastern population of Percina uranidea, known also as the stargazing darter, which is not considered endangered.

Dr. Near contends that early researchers “squinted their eyes a bit” when describing the fish, because it represented a way to fight the Tennessee Valley Authority’s plan to build the Tellico Dam on the Little Tennessee River, about 20 miles southwest of Knoxville.

“I feel it was the first and probably the most famous example of what I would call the ‘conservation species concept,’ where people are going to decide a species should be distinct because it will have a downstream conservation implication,” Dr. Near said.

The T.V.A. began building the Tellico Dam in 1967. Environmentalists, lawyers, farmers and the Cherokee, whose archaeological sites faced flooding, were eager to halt the project. In August 1973, they stumbled upon a solution.

David Etnier, a dam opponent and a zoologist at the University of Tennessee, went snorkeling with students in the Little Tennessee River at Coytee Spring, not far from Tellico. There, they found a fish on the river bottom that Dr. Etnier said he had never seen before, and he named it the snail darter.

This brilliant ploy has become standard practice among NIMBYists, so let me describe it more clearly.

Paywall here. 2008 words after the break.

If you are opposed to a property development, you get a naturalist and his grad students to pore over the terrain looking for any obscure species, no matter how insignificant.

When they find some little known thing, they go to the Fish and Wildlife service and ask for it to be protected as endangered.

Now, it’s up to the developers to, in return, show it’s not endangered, which it might not be, but nobody has been looking for it. So where do you find it growing? It turns out to often be easier to find some thing on a piece of land than go find that thing in the rest of the world.

For example, in 1989, Home Savings announced plans to build 3,050 homes on their Ahmanson Ranch in pricey Ventura County. But neighbors, such as actor Martin Sheen, not wanting more traffic to slow down their commutes, tried to block the development. The neighboring city of Calabasas, home to many Kardashian-level celebrities, sued to prevent groundbreaking.

A key roadblock was a botanist “accidentally” rediscovering on the property at the height of the controversy in 1999 the San Fernando Valley spineflower, a small ugly weed:

The San Fernando Valley spineflower had been described once in its existence, in a 1929 book. So opponents of the development spun that as that it had been thought to be extinct since 1929.

But I haven’t seen anybody presenting any evidence that anybody had missed it since 1929 and had been searching frantically for it. It would seem more likely than once one guy in 1929 got credit for naming the San Fernando Valley spineflower as a variety of the San Bernardino spineflower, nobody cared about it until it became a weapon to stop a development that would slow down Martin Sheen’s commute to the set of The West Wing.

So in 2003, the developers sold the land to the government to be a park. I went hiking there once. It was pretty, but I came home covered in ticks.

I hate ticks.

Since then, the San Fernando Valley spineflower has been discovered on one other location, which just happens to be another controversial housing development in the region, the Newhall Ranch.

And is the San Fernando Valley spineflower actually a separate species? It appears to be listed as a “variety” or race of the San Bernardino spineflower.

Back to the NYT on the snail darter:

The fish became a “David” to pit against “Goliath” — because if it were to be protected under the Endangered Species Act, the dam’s construction would be blocked.

… “This two-inch fish, which surely kept the lowest profile of all God’s creatures until a few years ago, has been the bane of my existence and the nemesis of what I fondly hoped would be my golden years,” Senator Howard H. Baker Jr. of Tennessee said about the snail darter in 1979. …

After the Supreme Court upheld the protection of the snail darter, President Jimmy Carter signed a bill that exempted the Tellico Dam from the Endangered Species Act. The dam began operating in 1979.

But the precedent had been set. Since then, disputes over what qualifies as a species come up all the time in big money Endangered Species Act disputes.

How about the red wolf? Is this coyote-wolf hybrid a distinct species worth expending large amounts of resources to preserve because if it goes extinct it will never come back. Or is the red wolf just what you get anew all the time when coyotes and wolves mate?

The feds eventually decided that because there was evidence that red wolves tended to preferentially mate with each other rather than at random, then there was evidence that the Endangered Species Act applied to them.

Seems reasonable on a good-enough-for-government-work basis.

Jeffrey Simmons, an author of the study who formerly worked as a biologist at the T.V.A., discovered what appeared to be snail darters in 2015 on the border of Alabama and Mississippi, far from the Tellico Dam.

Similarly, there could well be San Fernando Valley spineflowers here and there all over — the weed looks vaguely familiar even to me — but why would anybody bother looking for it?

Back to the NYT:

“Holy crap, do you know what this is?” Mr. Simmons said to a colleague in the creek that day.

Mr. Simmons knew it shouldn’t be there if it were truly a snail darter.

Ava Ghezelayagh, now at the University of Chicago, and colleagues conducted analysis of the fish’s DNA and compared snail darter physical traits with other fish. That led to confirmation that it was a match with the stargazing darter.

Dr. Plater, who also argued successfully for the fish in the Supreme Court case, took issue with the Yale study. He said the approach favored by Dr. Near and colleagues makes them genetic “lumpers” instead of “splitters,” meaning they reduce species instead of making more.

Lumpers and splitters are inevitable in all natural sciences.

He believes the findings also lean too heavily on genetics.

Uh, yeah …

“Whether he intends it or not, lumping is a great way to cut back on the Endangered Species Act,” Dr. Plater said of Dr. Near.

Dr. Near said being described as a “lumper” was a pejorative in his world, and he added that most of the research he and colleagues had performed had resulted in speciation splits, including a 2022 study.

Similarly, is the rare California gnatcatcher, an awkward little bird which shut down all sorts of developments in Southern California around the turn of the century, a separate endangered species? Or is it just a racial variant of the common Baja gnatcatcher?

The gnatcatcher controversy is a big part of the crazy story of the Trump National Los Angeles Golf Club, which Donald Trump bought out of bankruptcy after the 18th hole more or less fell into the Pacific. From a UPI story I wrote in 2001 on the benefit of environmentalism to wealthy homeowners.

With a partner (since bought out), Ed Zuckerman's sons Ken and Bob acquired 260 acres, giving them over a mile of shoreline [on Los Angeles County’s beautiful Palos Verdes Peninsula]. The crucial question then became how many of those acres they could actually use for home sites and a golf course.

At that point, the California gnatcatcher, a two-inch long, not very aerodynamic bird that lives in the scrubby gray-green sagebrush along the coast, began to play an enormous role in the [real estate developer] Zuckermans' lives and fortunes.

According to [Ken] Zuckerman, "The gnatcatcher became the weapon to use against the Irvine Corporation to stop development in Orange County." Vast amounts of money hinged on the arcane biological and legal question of whether the California gnatcatcher is different enough from the Baja Gnatcatcher to deserve protection under the Endangered Species Act. While only 4,000 or so California gnatcatchers exist, there are hundreds of thousands of Baja gnatcatchers.

In the 1980s, an ornithologist named Jonathan Atwood announced that he believed they were all the same.

"At the Sierra Club's request, however, Atwood looked at it again and decided they were different," Zuckerman said.

The ornithologist found statistical evidence that gnatcatchers in California tended to differ in "darkness" from those in Baja.

As do human beings in Baja and Alta California, but that doesn’t make them different species.

Based on Atwood's new recommendation, in 1993 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared the California version a protected species. They put stringent limitations on development of 400,000 acres of prime Southern California real estate. In 2000 a new DNA study co-authored by Atwood found "no differences that would place the two birds in different subspecies."

In the early 1990s, however, the Zuckermans correctly foresaw that "the handwriting was on the wall that the California gnatcatcher would be listed as endangered." He recounted, "We were interested spectators. We made the decision that we didn't want to gamble so we went to the government and said, 'Make us a deal on the assumption that the California gnatcatcher is listed.'"

They were told to prove they could grow from seeds the kind of sagebrush that the gnatcatcher likes. …

The property had been a garbanzo bean farm since the 19th Century, so all the native sagebrush was gone.

The Zuckermans devoted the next two years to growing a five-acre garden of the rather foreboding sage scrub.

When that proved successful, they brought Atwood out to ask for his approval on the development. "We invited him to walk the property with Pete Dye," who is widely considered the most important golf architect of the last three decades, Zuckerman said.

"Fortunately, they struck it off very well. When they came back they had cut a deal in their minds."

The agreement required the Zuckermans to grow sagebrush from seed in three preserves and in fingers of "habitat" between the fairways. Currently, about 10 pairs of gnatcatchers nest in the carefully tended sagebrush.

"It's nice to know that all that work has at least paid off in terms of birds nesting there," the developer said….

Ultimately, out of the Zuckerman's 260 acres, 75 are devoted to the 75 home sites. The golf course is built on 100 acres (compared with 150 for a typical course), but 20 of those were required to be covered with regrown sagebrush. So, 105 acres are reserved for sagebrush, public parks, or pathways.

A general rule of thumb is that environmental restrictions tend to make developments more beautiful and more expensive. Not surprisingly, to recoup this huge investment, Ocean Trails' prices must be high. Home sites start at about $1 million. When all 18 holes are finished, Zuckerman hopes to be able to charge the same $250 weekend greens fee as the Pelican Hill courses in Orange County.

Tee times on Monday, January 6, 2025 range from $575 per golfer for prime morning times to $275 in late morning.

Environmentalism's elitist effects are also seen in the difficulty of the golf course.

The sagebrush grown between fairways to benefit the gnatcatcher makes it easy for the amateur player to lose golf balls. On the day of the landslide, the U.S. Golf Association was giving Ocean Trails a course rating. The preliminary "slope" rating, which indicates how hard the course is for a bogey golfer, is 154, just under the maximum limit of 155.

It’s still a fairly successful golf course today, but it would be more fun without flesh-ripping sagebrush between each fairway.

When Trump bought the course from the Zuckerman Brothers in 2005, he brought in a Ladies Professional Golf Association tournament and promoted it energetically. But the strips of sagebrush planted to host the California gnatcatcher led to numerous lost balls, leading to six hour rounds for the pros, and made it hard for spectators to get around.

Zuckerman said, "If you knew how difficult this project would be, you never would have started; but once you do, you become a hostage to the project. It becomes your career. I've spent 10 years on it."

Brightening, he went on, "I've lived here since 1971 and raised my family here. I get a special feeling doing something for my community. People appreciate that we've persevered. They come down here and see something special and beautiful and it makes them proud to have it in their community. And that makes me feel good."

In the 21st Century, one dogma of midwit conventional wisdom has become that The Science has proven that race does not exist, scientifically.

What people seem to mean when they say this is that racial categories don’t have bright-line borders that way that, say, many legal categories try to leave no grey area around whether you are old enough to vote or not. To many people, “science” means “precise.” After all, nature can’t be messy.

And yet it is.

Not many comments on the snail darter article. They’re all over at a story about newly introduced congestion pricing in NYC.

Most popular: “This is the problem when the experts are also "activists." You don't get an objective truth. This guy didn't want the dam and made up a reason to prevent it. The problem is there is trickle down effect to other "expert" opinions. People begin to doubt.”

If Zuckerberg was relying on Pete Dye to butter up the naturalist that was a bad move. Pete was pricklier than the sagebrush. If he got Pete's wife Alice to do it then he deserves his fortune.