Male vs. Female Novelists

Why do men tend to be so much more concerned than women about identifying the Greatest of All Time?

From the New York Times opinion section:

The Disappearance of Literary Men Should Worry Everyone

Dec. 7, 2024, 7:00 a.m. ET

By David J. Morris

Mr. Morris teaches creative writing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Over the past two decades, literary fiction has become a largely female pursuit. Novels are increasingly written by women and read by women. In 2004, about half the authors on the New York Times fiction best-seller list were women and about half men; this year, the list looks to be more than three-quarters women. According to multiple reports, women readers now account for about 80 percent of fiction sales.

I see the same pattern in the creative-writing program where I’ve taught for eight years. About 60 percent of our applications come from women, and some cohorts in our program are entirely female. When I was a graduate student in a similar program about 20 years ago, the cohorts were split fairly evenly by gender. As Eamon Dolan, a vice president and executive editor at Simon & Schuster, told me recently, “the young male novelist is a rare species.”

Male underrepresentation is an uncomfortable topic in a literary world otherwise highly attuned to such imbalances. In 2022 the novelist Joyce Carol Oates wrote on Twitter that “a friend who is a literary agent told me that he cannot even get editors to read first novels by young white male writers, no matter how good.” The public response to Ms. Oates’s comment was swift and cutting — not entirely without reason, as the book world does remain overwhelmingly white. But the lack of concern about the fate of male writers was striking.

Then comes a bunch of Please Don’t Cancel Me stuff:

To be clear, I welcome the end of male dominance in literature. Men ruled the roost for far too long, too often at the expense of great women writers who ought to have been read instead.

Such as?

When the first generation of overtly feminist literature professors started talking about expanding the literary canon in the 1970s-1980s to include more books by women authors, they kept coming up with already world-famous books like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, for which they made a reasonable case that popular works of such massive impact deserve to be taken more seriously by academia.

It’s not like they discovered a lot of old-time women writer radical stylistic innovators who had been overlooked by professors. Virginia Woolf, an early stream-of-consciousness writer, was already so important in English Lit circles before 1970s feminism that Elizabeth Taylor won the Best Actress Oscar for her role in the 1966 movie about academics entitled “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”

I also don’t think that men deserve to be better represented in literary fiction; they don’t suffer from the same kind of prejudice that women have long endured.

Well, if you want men to buy and read new novels rather than just play Call of Duty, they’ll need representation. The publishing industry’s aversion toward selling novels to men is kind of like if the Coca-Cola corporation decided that it wasn’t going to try hard to sell Coke in the American South anymore because Southerners’ ancestors have gotten to enjoy Coke longer than anybody else, so forget the latest generation. Or something.

Furthermore, young men should be reading Sally Rooney and Elena Ferrante.

How sure are we that the author or authors of the “Elena Ferrante” novels about a girl growing up working class in Naples is 100% a woman?

It seems to me about equally likely that the pseudonymous “Elena Ferrante” is either a female professional translator who was, admittedly, a girl, but who grew up upper middle class in Rome; or her husband, a famous Italian novelist who grew up working class in the Naples area; or, my guess, both working as a team.

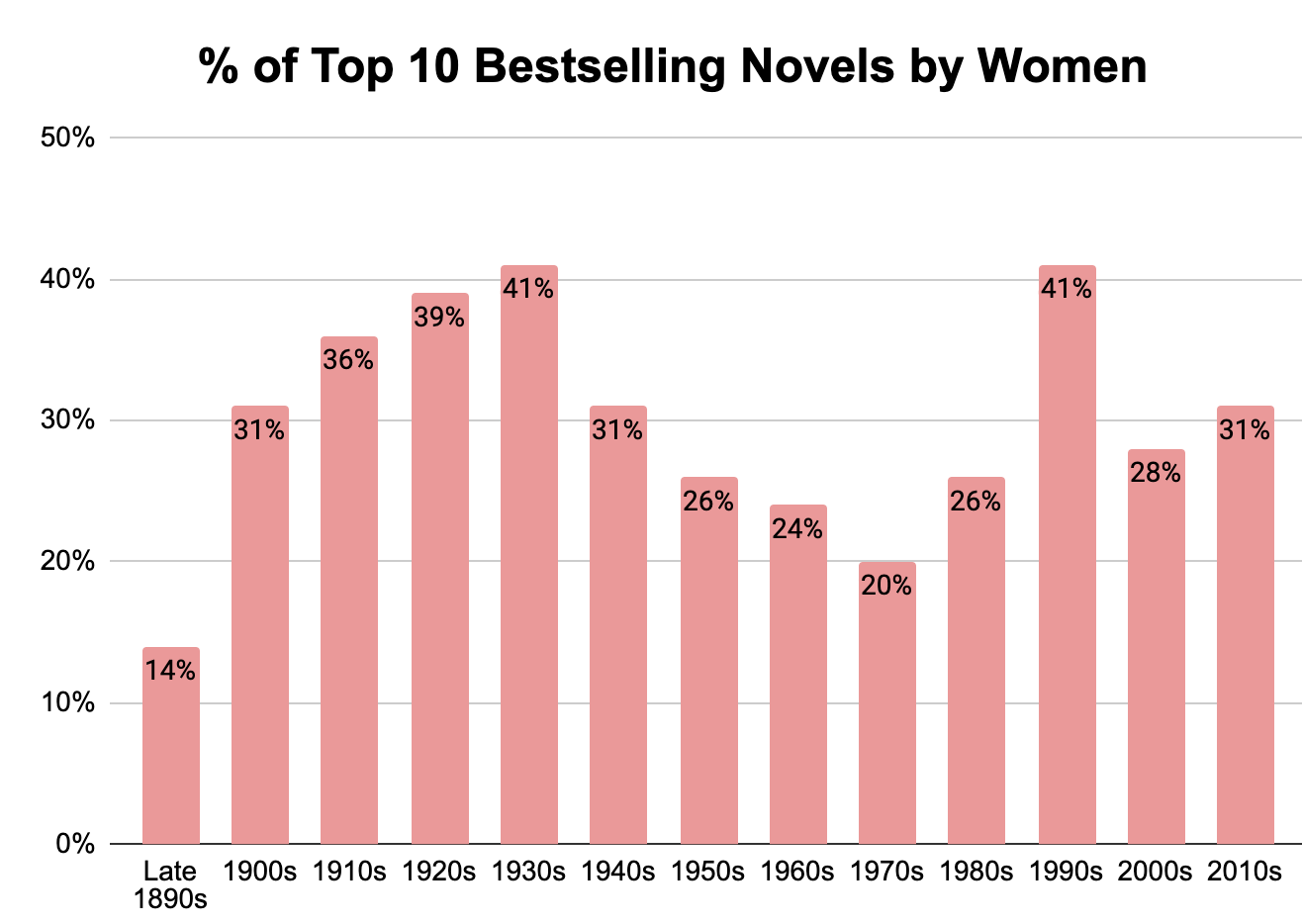

The secret of women’s literature is that women wrote a very sizable fraction of the popular bestselling novels of the last 250 years, but a smaller percentage of the ultra-ambitious immortal masterpieces. I found the Publisher’s Weekly list of top 10 bestselling novels each year from the mid-1890s onward. The first four decades of the 20th Century were particularly prosperous times for women novelists:

For example, in P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Bertie Wooster stories, an increasing fraction of which are in the public domain, lady novelist Rosie M. Banks comes up fairly frequently. The character was perhaps based on romance novelist Ruby M. Ayres, whose “Partial Bibliography” in Wikipedia lists 70 novels, and the article says she published 135 novels.

In 1921’s “Jeeves in the Springtime,” Bertie’s Drones Club pal Bingo Little falls in love with a waitress named Mabel, and asks Bertie to get his valet Jeeves to advise him on how he can get his rich uncle to approve of his marriage to this working class girl and raise his allowance.

Bingo Little’s uncle is a fat gourmand who has come down with gout due to his over-indulgence in his cook Jane’s superb skills. Jeeves tells Bertie:

"No, sir, I fancy that the elder Mr. Little's misfortune may be turned to the younger Mr. Little's advantage. I was speaking only the other day to Mr. Little's valet, and he was telling me that it has become his principal duty to read to Mr. Little in the evenings. If I were in your place, sir, I should send young Mr. Little to read to his uncle."

"Nephew's devotion, you mean? Old man touched by kindly action, what?"

"Partly that, sir. But I would rely more on young Mr. Little's choice of literature."

"That's no good. Jolly old Bingo has a kind face, but when it comes to literature he stops at the Sporting Times."

"That difficulty may be overcome. I would be happy to select books for Mr. Little to read. Perhaps I might explain my idea further?"

"I can't say I quite grasp it yet."

"The method which I advocate is what, I believe, the advertisers call Direct Suggestion, sir, consisting as it does of driving an idea home by constant repetition. You may have had experience of the system?"

"You mean they keep on telling you that some soap or other is the best, and after a bit you come under the influence and charge round the corner and buy a cake?"

"Exactly, sir. The same method was the basis of all the most valuable propaganda during the recent war.

Wodehouse was quietly anti-war and anti-imperial.

“I see no reason why it should not be adopted to bring about the desired result with regard to the subject's views on class distinctions. If young Mr. Little were to read day after day to his uncle a series of narratives in which marriage with young persons of an inferior social status was held up as both feasible and admirable, I fancy it would prepare the elder Mr. Little's mind for the reception of the information that his nephew wishes to marry a waitress in a tea-shop."

"Are there any books of that sort nowadays? The only ones I ever see mentioned in the papers are about married couples who find life grey, and can't stick each other at any price."

It’s natural to assume that 100% of Bertie’s slang vocabulary is that of an Edwardian Eton old boy, but some of it is pre-WWI Broadway vocabulary. Wodehouse spent several years in New York co-writing Broadway musicals in the George M. Cohan era before the Great War, so Bertie’s style is a unique Anglo-American argot. (Another Dulwich College boy, Los Angeles detective writer Raymond Chandler, is also an Anglo-American genre great.)

"Yes, sir, there are a great many, neglected by the reviewers but widely read. You have never encountered 'All for Love," by Rosie M. Banks?"

"No."

"Nor 'A Red, Red Summer Rose,' by the same author?"

"No."

"I have an aunt, sir, who owns an almost complete set of Rosie M. Banks'. I could easily borrow as many volumes as young Mr. Little might require. They make very light, attractive reading."

"Well, it's worth trying."

"I should certainly recommend the scheme, sir."

"All right, then. Toddle round to your aunt's to-morrow and grab a couple of the fruitiest. We can but have a dash at it."

"Precisely, sir."

* * * * *

Bingo reported three days later that Rosie M. Banks was the goods and beyond a question the stuff to give the troops. Old Little had jibbed somewhat at first at the proposed change of literary diet, he not being much of a lad for fiction and having stuck hitherto exclusively to the heavier monthly reviews; but Bingo had got chapter one of "All for Love" past his guard before he knew what was happening, and after that there was nothing to it. Since then they had finished "A Red, Red Summer Rose," "Madcap Myrtle" and "Only a Factory Girl," and were halfway through "The Courtship of Lord Strathmorlick."

… Anyhow, things seemed to be buzzing along quite satisfactorily, and Bingo said he had got an idea which, he thought, was going to clinch the thing. He wouldn't tell me what it was, but he said it was a pippin.

"We make progress, Jeeves," I said.

"That is very satisfactory, sir."

"Mr. Little tells me that when he came to the big scene in 'Only a Factory Girl,' his uncle gulped like a stricken bull-pup."

"Indeed, sir?"

"Where Lord Claude takes the girl in his arms, you know, and says----"

"I am familiar with the passage, sir. It is distinctly moving. It was a great favourite of my aunt's."

"I think we're on the right track."

"It would seem so, sir."

"In fact, this looks like being another of your successes. I've always said, and I always shall say, that for sheer brain, Jeeves, you stand alone. All the other great thinkers of the age are simply in the crowd, watching you go by."

"Thank you very much, sir. I endeavour to give satisfaction."

About a week after this, Bingo blew in with the news that his uncle's gout had ceased to trouble him, and that on the morrow he would be back at the old stand working away with knife and fork as before.

"And, by the way," said Bingo, "he wants you to lunch with him tomorrow."

"Me? Why me? He doesn't know I exist."

"Oh, yes, he does. I've told him about you."

"What have you told him?"

"Oh, various things. Anyhow, he wants to meet you. And take my tip, laddie--you go! I should think lunch to-morrow would be something special."

I don't know why it was, but even then it struck me that there was something dashed odd--almost sinister, if you know what I mean--about young Bingo's manner. The old egg had the air of one who has something up his sleeve.

"There is more in this than meets the eye," I said. "Why should your uncle ask a fellow to lunch whom he's never seen?"

"My dear old fathead, haven't I just said that I've been telling him all about you--that you're my best pal--at school together, and all that sort of thing?"

"But even then--and another thing. Why are you so dashed keen on my going?"

Bingo hesitated for a moment.

"Well, I told you I'd got an idea. This is it. I want you to spring the news on him. I haven't the nerve myself."

"What! I'm hanged if I do!"

"And you call yourself a pal of mine!"

"Yes, I know; but there are limits."

"Bertie," said Bingo reproachfully, "I saved your life once."

"When?"

"Didn't I? It must have been some other fellow, then. Well, anyway, we were boys together and all that. You can't let me down."

"Oh, all right," I said. "But, when you say you haven't nerve enough for any dashed thing in the world, you misjudge yourself. A fellow who----"

"Cheerio!" said young Bingo. "One-thirty to-morrow. Don't be late."

* * * * *

[Bingo’s uncle said] … "Mr. Wooster, I am gratified--I am proud--I am honoured."

It seemed to me that young Bingo must have boosted me to some purpose.

"Oh, ah!" I said.

He stepped back a bit, still hanging on to the good right hand.

"You are very young to have accomplished so much!"

I couldn't follow the train of thought. The family, especially my Aunt Agatha, who has savaged me incessantly from childhood up, have always rather made a point of the fact that mine is a wasted life, and that, since I won the prize at my first school for the best collection of wild flowers made during the summer holidays, I haven't done a dam' thing to land me on the nation's scroll of fame. I was wondering if he couldn't have got me mixed up with someone else, when the telephone-bell rang outside in the hall, and the maid came in to say that I was wanted. I buzzed down, and found it was young Bingo.

"Hallo!" said young Bingo. "So you've got there? Good man! I knew I could rely on you. I say, old crumpet, did my uncle seem pleased to see you?"

"Absolutely all over me. I can't make it out."

"Oh, that's all right. I just rang up to explain. The fact is, old man, I know you won't mind, but I told him that you were the author of those books I've been reading to him."

"What!"

"Yes, I said that 'Rosie M. Banks' was your pen-name, and you didn't want it generally known, because you were a modest, retiring sort of chap. He'll listen to you now. Absolutely hang on your words. A brightish idea, what? I doubt if Jeeves in person could have thought up a better one than that. Well, pitch it strong, old lad, and keep steadily before you the fact that I must have my allowance raised. I can't possibly marry on what I've got now. If this film is to end with the slow fade-out on the embrace, at least double is indicated. Well, that's that. Cheerio!"

… Old Little struck the literary note right from the start.

"My nephew has probably told you that I have been making a close study of your books of late?" he began.

"Yes. He did mention it. How--er--how did you like the bally things?"

He gazed reverently at me.

"Mr. Wooster, I am not ashamed to say that the tears came into my eyes as I listened to them. It amazes me that a man as young as you can have been able to plumb human nature so surely to its depths; to play with so unerring a hand on the quivering heart-strings of your reader; to write novels so true, so human, so moving, so vital!"

"Oh, it's just a knack," I said. …

"Let me tell you, Mr. Wooster, that I appreciate your splendid defiance of the outworn fetishes of a purblind social system. I appreciate it! You are big enough to see that rank is but the guinea stamp and that, in the magnificent words of Lord Bletchmore in 'Only a Factory Girl,' 'Be her origin ne'er so humble, a good woman is the equal of the finest lady on earth!'"

I sat up.

"I say! Do you think that?"

"I do, Mr. Wooster. I am ashamed to say that there was a time when I was like other men, a slave to the idiotic convention which we call Class Distinction. But, since I read your books----"

I might have known it. Jeeves had done it again.

"You think it's all right for a chappie in what you might call a certain social position to marry a girl of what you might describe as the lower classes?"

"Most assuredly I do, Mr. Wooster."

I took a deep breath, and slipped him the good news.

"Young Bingo--your nephew, you know--wants to marry a waitress," I said.

"I honour him for it," said old Little.

"You don't object?"

"On the contrary."

I took another deep breath and shifted to the sordid side of the business.

"I hope you won't think I'm butting in, don't you know," I said, "but--er--well, how about it?"

"I fear I do not quite follow you."

"Well, I mean to say, his allowance and all that. The money you're good enough to give him. He was rather hoping that you might see your way to jerking up the total a bit."

Old Little shook his head regretfully.

"I fear that can hardly be managed. You see, a man in my position is compelled to save every penny. I will gladly continue my nephew's existing allowance, but beyond that I cannot go. It would not be fair to my wife."

"What! But you're not married?"

"Not yet. But I propose to enter upon that holy state almost immediately. The lady who for years has cooked so well for me honoured me by accepting my hand this very morning." A cold gleam of triumph came into his eye. "Now let 'em try to get her away from me!" he muttered, defiantly.

And then a whole bunch more happens in succeeding stories.

Wodehouse wasn’t the most masculine of male novelists, but he was something of a genius at what he did, so he still has some fanboys like me a century later.

There’s a masculine urge to identify the Greatest of All Time, even if in some narrow niche. If you define Wodehouse’s genre narrowly enough, he’s clearly the GOAT of whatever that type of writing is.

In contrast, fangirls aren’t that nostalgic and not that focused on determining the GOAT. They have Jane Austen, but in general, women fans are more Latest Thing-oriented, looking for what’s new. This leads to a lot of pretty good books by women, but fewer great ones.

"This leads to a lot of pretty good books by women, but fewer great ones"

It's intriguing how often this pattern plays out: Men at the extreme ends of success and failure, with a higher proportion of woman in the middle of the curve. Men lead armies far more often than women, but get slaughtered at a higher rate. Men create world-shifting startups and sit on Fortune 500 boards at higher rates than women, but are also more likely to end up addicted to who knows what while living in a sidewalk tent.

How much is the absence of men in literature due to female takeover versus men just dropping out in favor of newer forms of entertainment like video games, social media, etc.?

Thanks for the Wodehouse post, Steve.

I'm a Wodehouse fan, and still read his novels. I find them ideal for airplane/holiday reading, and now that much of his work is out of copyright, you can load up the Kindle with Wodehouse as lavishly as you wish.

I know what you mean about his genre. I would go perhaps a little further, and say he's the best purely comic *novelist* I've read. Many comic authors are funny in stretches, but they overshoot, overwrite, and become a bit tiresome, especially at novel length.

Wodehouse is the master of finely-judged restraint. He manipulates a small range of settings, character types, and plot devices. He deals constantly with the absurd -- wonderfully, hilariously -- but he never surrenders to incongruous description or locution. Wodehouses's literary wineskins constantly bulge at the seams with sheer preposterous joy, but they burst only at rare -- and hence unforgettable -- apogees, e.g. Gussie Fink-Nottle's run at the school prize-giving ceremony. It's like an old-timey movie boiler with its gauges red-lined non-stop. No one else I've read can maintain this delicate balance.