Must We Still Pretend Ta-Nehisi Coates Wrote The Century's 36th Best Book?

If the New York Times’ new choices are really the 100 best books of the first quarter of this century … uh-oh …

The New York Times recruited 500+ “literary luminaries” to cast votes (rather prematurely) on the best books of the first 25 years of this century.

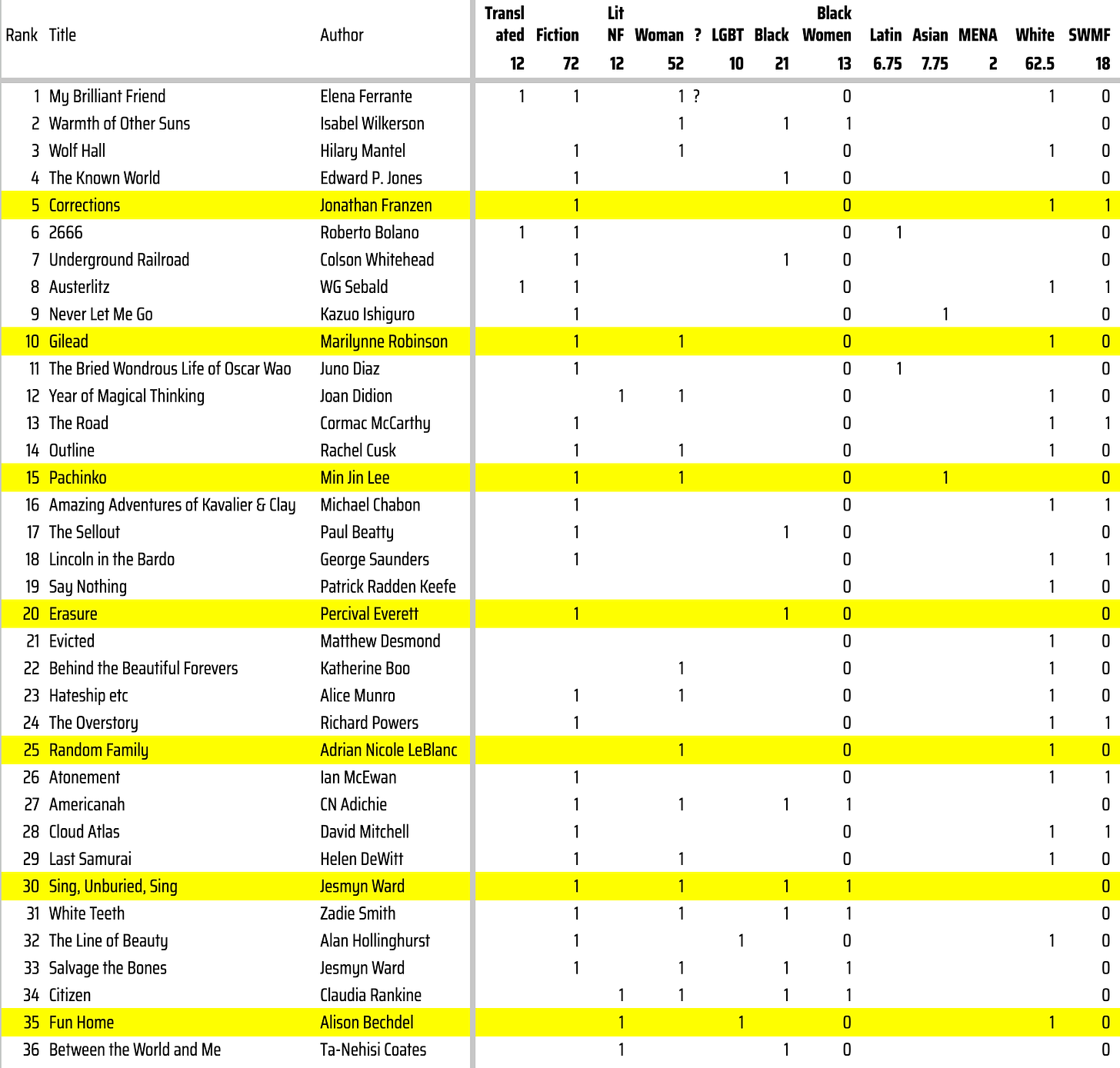

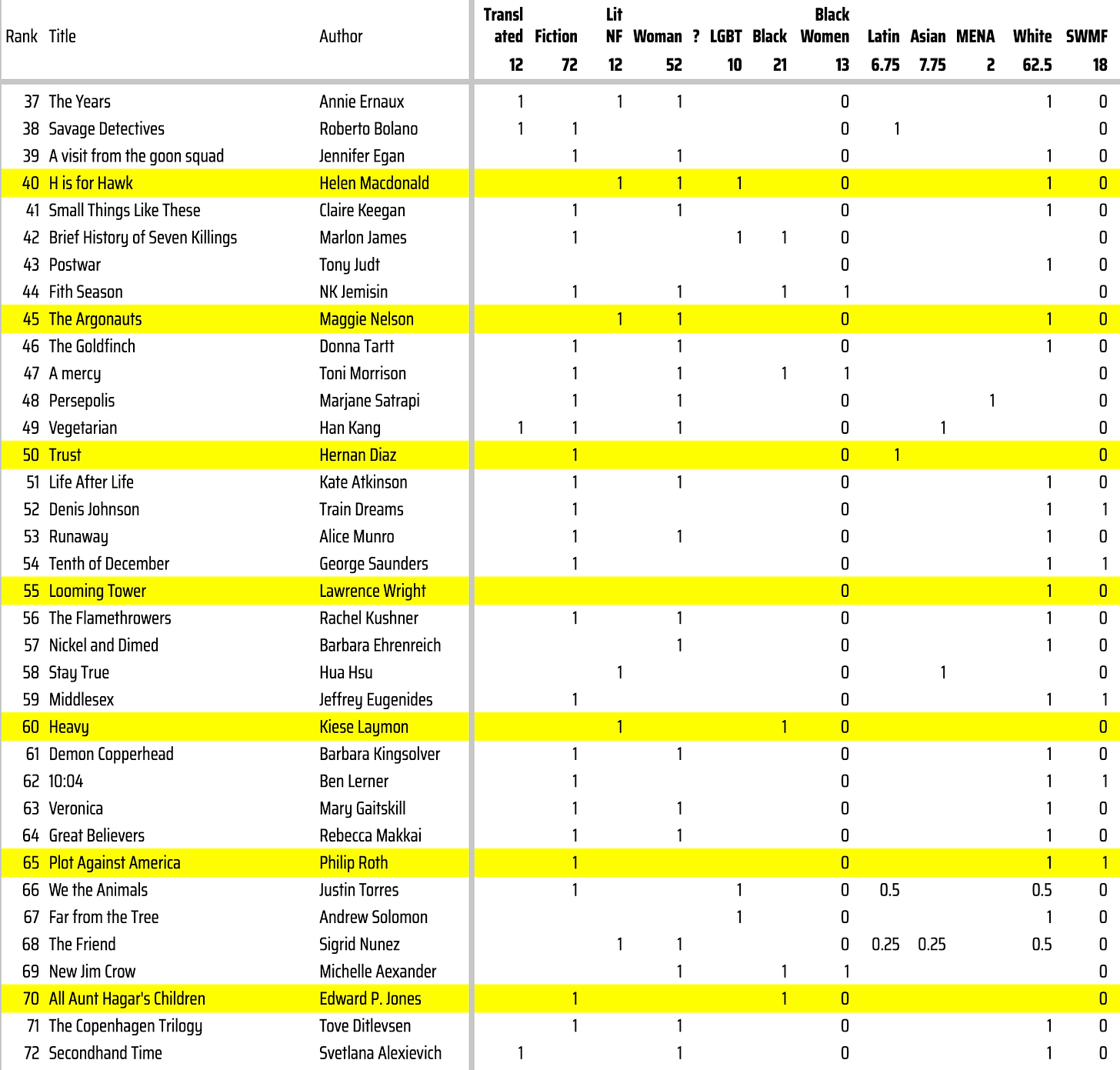

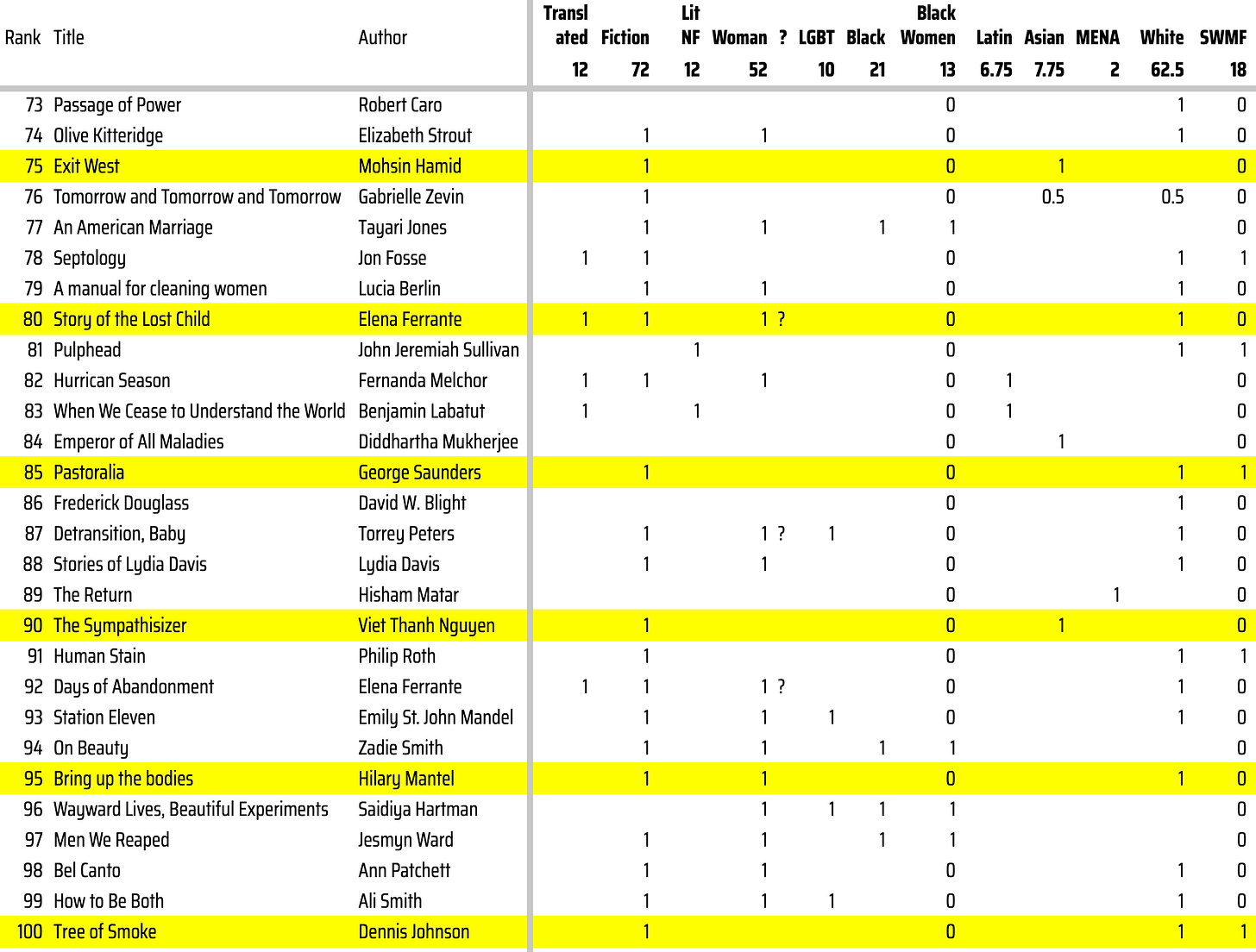

Here is the top 36 of their list:

The voting was heavily tilted toward fiction (72 of the top 100) plus a vague category I call literary nonfiction, with 12 more picks.

What do I mean by literary nonfiction? Whereas you might read Walter Isaacson’s biographies Elon Musk or Steve Jobs (neither of which made the NYT’s Top 100 list) because you want to learn about Elon Musk or Steve Jobs because they are important and interesting (and the fact that Isaacson’s books are well-done is just a bonus); in contrast, literary nonfiction are books, like the Official 36th Best Book of This Century, Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, that you’d read not because you are dying to find out more about that world-historical Escalator Incident involving Ta-Nehisi Coates’ kid and the mean white lady who said “C’mon,” but because lots of people told you TNC was a great writer and thinker.

It would have been better if the NYT had simply specified that this contest was only for fiction and highly literary nonfiction, and then conducted a separate contest for the Pinkers and Pikettys and the like.

#1 is My Brilliant Friend by the pseudonymous Elena Ferrante who writes about girls growing up in Naples. Ferrante is likely some combination of an Italian literary couple, interpreter Anita Raja and her more famous husband, novelist Domenico Starnone. They upgraded their lifestyle lavishly just when Elena Ferrante’s royalties started pouring in. As I wrote in 2021:

If you assume the wife is the The Author, then it’s only natural to wonder how much help she got from her talented husband, the well-regarded novelist?

But if you assume the husband is The Author, then it’s only natural to wonder how much help he got from his skilled wife, the professional translator?

Maybe the husband always enjoyed help with his novels from his wife. Maybe the wife copy-edited her husband’s early novels into their current style, the way editor Gordon Lish edited short story author Raymond Carver into his famous style?

There are a lot of possibilities.

For example, in the Coen Brother’s 1941 Hollywood movie Barton Fink, the William Faulkner character (John Mahoney) is picking up paychecks as a screenwriter but is usually roaring drunk by mid-day. Yet his devoted secretary/mistress (Judy Davis) keeps turning in the required number of pages by 5 pm. Eventually she admits to Barton (John Turturro) that she wrote the great man’s last two novels. …

In real life, he-man writer-director John Huston’s career was increasingly facilitated by the screenwriting skills of his secretary Gladys Hill. She eventually earned an Oscar nomination for co-writing The Man Who Would Be King with Huston.

It strikes me as plausible that a husband-wife team might write good novels together. It used to be common in Golden Age Hollywood for male-female teams to work together. But writing teams are not at all in fashion in literary circles: none of the other Top 100 is team-written. So it could be that the couple chose to use a pseudonym because of literary prejudice against writing teams.

The top 100 are pretty evenly split among men and women, depending upon how you feel about the three Ferrante novels and the novel Detransition, Baby by an ex-man.

Only 12 of the 100 are books in translation. Maybe they should have just limited the list to books published originally in English. On the other hand, the handful of translated books by Ferrante, Bolano, Sebald, Ernaux, Kang, Fosse, Melchor, Labatut, and Alexievich are probably really good to over the contests’ bias toward English language books.

21 of the top 100 are by blacks. Does anybody really think blacks wrote 21% of the best books of this century? And of course almost all the books by blacks are about blacks. (Zadie Smith is a rare black writer who doesn’t always write about blacks.)

I haven’t read #2 The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson, but I reviewed her next bestseller, Caste:

First, Wilkerson’s moralistic prose style appears to be aimed at the Intelligent Middle Schooler market: It’s young-adult nonfiction. It’s not badly written…, it’s just not for self-respecting grown-ups.

Second, Wilkerson is not a terribly knowledgeable, insightful, or analytical thinker. Caste is a huge topic with a huge literature, and Wilkerson, a former human-interest journalist for The New York Times, is in over her head.

For example, Wilkerson writes about Jim Crow’s weird, Hindu-like concern with ritual pollution, which mandated separate drinking fountains and so forth. But unlike some previous writers on the topic, she fails to notice that this was a post–Civil War novelty that emerged among the defeated whites. Previously, slave-owners had lived on intimate terms with their house slaves and didn’t worry about such neurotic concerns, probably because their legal and political position was so dominant that they didn’t need to impose petty taboos to humiliate blacks.

But as the losers in the Civil War, Southern whites created Jim Crow to prevent their mulattoization in their new age of defeat. Wilkerson doesn’t perceive that the personal nastiness of Jim Crow toward blacks was a product less of Southern white dominance than of Southern white subordination to Northern whites, of that defeat that was for a century foremost in the minds of Southern whites.

Third, African-American authors’ leading genre has been autobiography (The Autobiography of Malcolm X is the most famous example, although my favorite is Zora Neale Hurston’s Dust Tracks on a Road), and Wilkerson’s book keeps digressing into personal anecdotes about people disrespecting her because of her

racecaste.But Wilkerson hasn’t lived as interesting of a life as, say, Frederick Douglass or Maya Angelou. Hence, many of her memories involve less-than-electrifying encounters with fellow passengers in first class who give her a funny look when she asks for help lifting her carry-on luggage or the like. In comparison, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Escalator Incident is as thrilling as The Count of Monte Cristo.

Among the 84 works of fiction and literary nonfiction, only 18 are by straight white men. The straight white male fiction writer with the most books in the top 100 with three is satirical short story writer George Saunders, a graduate of the Colorado School of Mines who reminds some readers of Kurt Vonnegut. I never heard of him but he sounds interesting.

Other non-Hispanic white guy writers to make the literature list include Jonathan Franzen, WG Sebald, Cormac McCarthy, Michael Chabon, Richard Powers, Ian McEwan, David Mitchell, Denis Johnson, Jeffery Eugenides, Ben Lerner, Philip Roth, Jon Fosse, and John Jeremiah Sullivan.

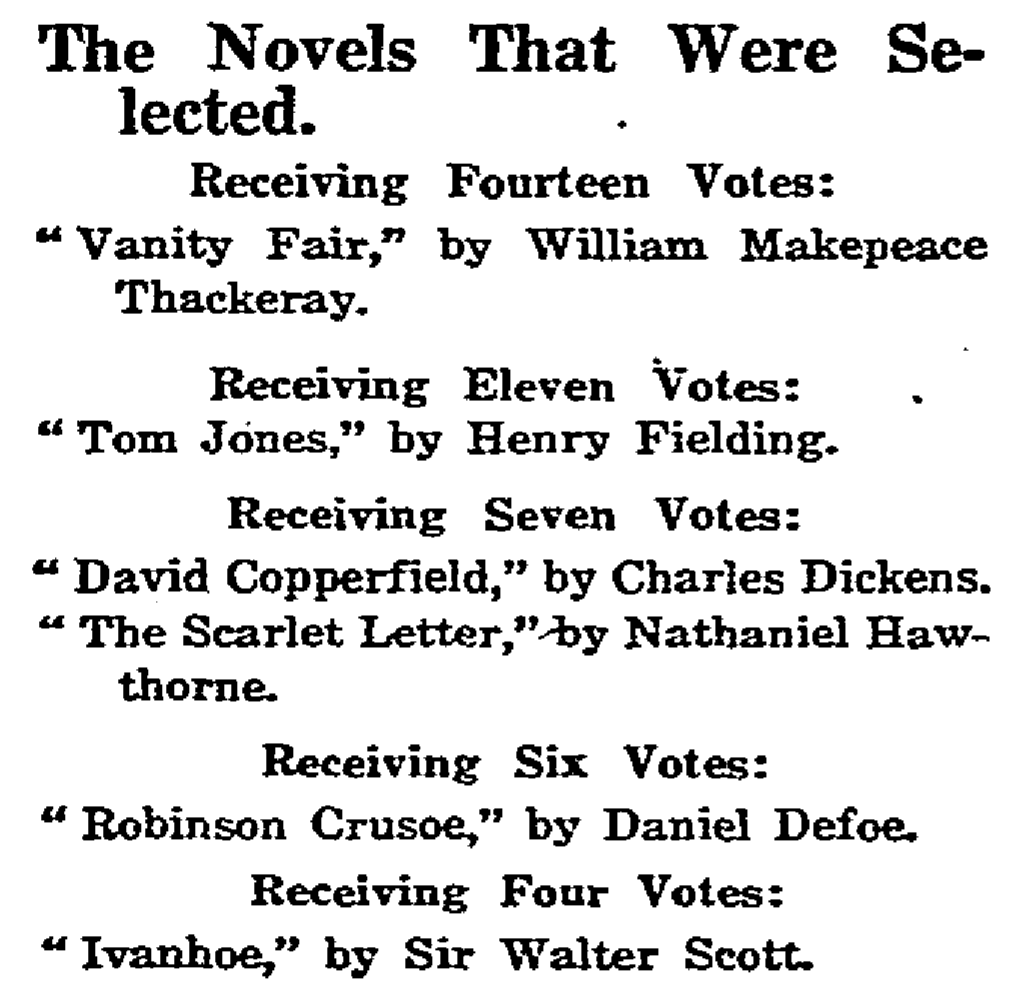

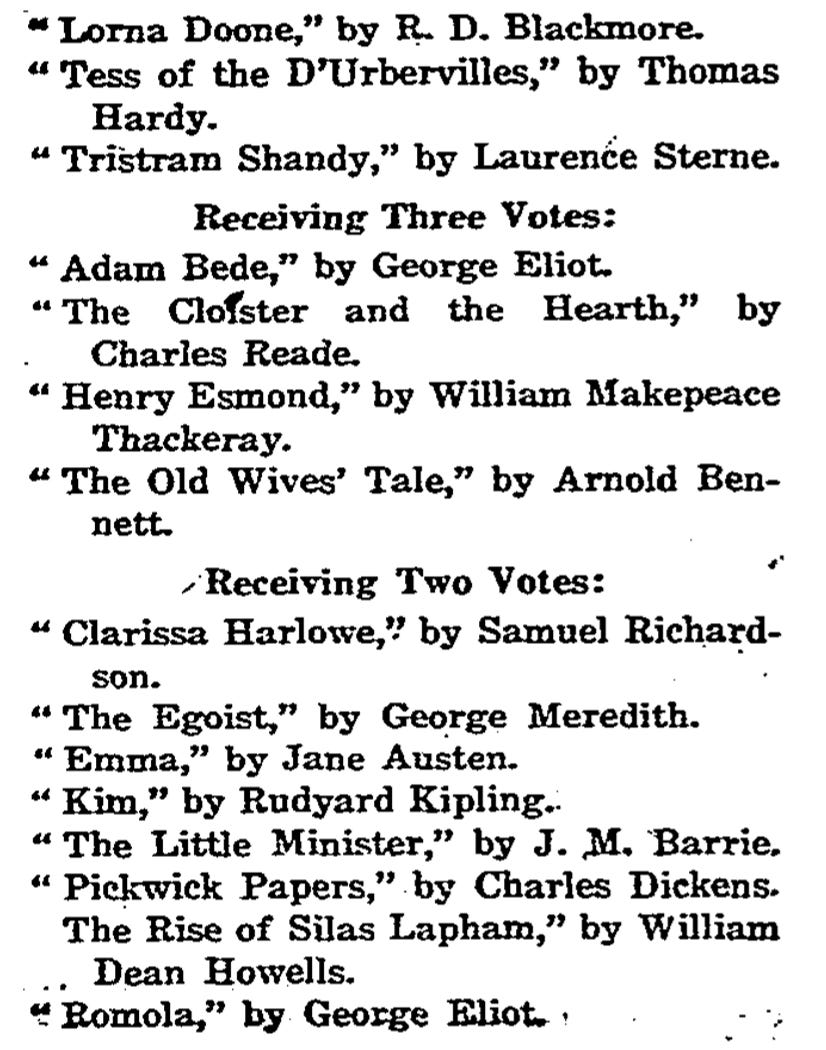

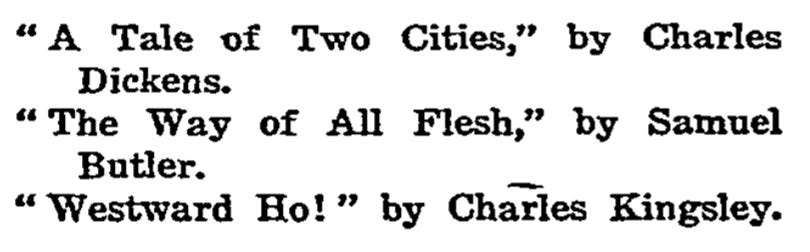

The New York Times ran a similar survey in 1915, but restricted the voting then to 28 novelists picking their favorite novels of all time. I’m unsure if they were restricted to English language novels or not: I don’t see Don Quixote. Or maybe pro-Anglophone prejudices were strong during the Great War.

The 1915 winner was William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1848 novel Vanity Fair, which I recently read (and reviewed) for the first time.

I read Tom Jones from 1751 (IIRC) in high school and vastly enjoyed it, especially the astonishing last 20 pages which adroitly wrap up the previous 780 pages of seemingly meandering plot. I tried to reread it recently, but I’m not patient enough anymore.

I thought The Scarlet Letter was a drag when I read it in high school. I was very much a literary Anglophile, greatly preferring British to American classic works.

The most modern-sounding novel on the 1915 list was D.H. Lawrence’s 1913 Sons and Lovers.

Many of the same authors would today make the same list, but with different books getting the most votes: e.g., Great Expectations would likely lead Charles Dickens’ novels, Pride and Prejudice would be out front among Jane Austen novels, and Middlemarch for George Eliot.

I suspect the NYT’s 1915 poll choices will endure longer than its 2024 poll choices.

We can know it's fake because "Noticing" is nowhere to be seen.

We need to stop pretending that we don't live in a civilisation who's intelligentsia has mostly disappeared up its own backside.