Should colleges demand DNA results from applicants?

Tyler Cowen stumps the NYT's genetics correspondent.

Tyler Cowen of Marginal Revolution interviews Carl Zimmer, the successor to the canceled Nicholas Wade as the genetics correspondent for the New York Times:

On using DNA for decision making

COWEN: Over time, how much will DNA information enter our daily lives? To give a strange example, imagine that, for a college application, you have to upload some of your DNA. Now to unimaginative people, that will sound impossible, but if you think about the equilibrium rolling itself out slowly — well, at first, students disclose their DNA, and over time, the DNA becomes used for job hiring, for marriage, in many other ways. Is this our future equilibrium, that genetic information will play this very large role, given how many qualities seem to be at least 40 percent to 60 percent inheritable, maybe more?

ZIMMER: The term that a scientist in this field would use would be heritable, not inheritable. Heritability is a slippery thing to think about. I write a lot about that in my book, She Has Her Mother’s Laugh, which is about heredity in general. Heritability really is just saying, “Okay, in a certain situation, if I look at different people or different animals or different plants, how much of their variation can I connect with variation in their genome?” That’s it. Can you then use that variability to make predictions about what’s going to happen in the future? That is a totally different question in many —

COWEN: But it’s not totally different. Your whole family’s super smart. If I knew nothing about you, and I knew about the rest of your family, I’d be more inclined to let you into Yale, and that would’ve been a good decision. Again, only on average, but just basic statistics implies that.

ZIMMER: You’re very kind, but what do you mean by intelligent? I’d like to think I’m pretty good with words and that I can understand scientific concepts. I remember in college getting to a certain point with calculus and being like, “I’m done,” and then watching other people sail on.

COWEN: Look, you’re clearly very smart. The New York Times recognizes this. We all know statistics is valid. There aren’t any certainties. It sounds like you’re running away from the science. Just endorse the fact you came from a very smart family, and that means it’s quite a bit more likely that you’ll be very smart too. Eventually, the world will start using that information, would be the auxiliary hypothesis. I’m asking you, how much will it?

ZIMMER: The question that we started with was about actually uploading DNA. Then the question becomes, how much of that information about the future can you get out of DNA? I think that you just have to be incredibly cautious about jumping to conclusions about it because the genome is a wild and woolly place in there, and the genome exists in environments. Even if you see broad correlations on a population level, as a college admission person, I would certainly not feel confident just scanning someone’s DNA for information in that regard.

COWEN: Oh, that wouldn’t be all you would do, right? They do plenty of other things now. Over time, say for job hiring, we’ll have the AI evaluate your interview, the AI evaluate your DNA. It’ll be highly imperfect, but at some point, institutions will start doing it, if not in this country, somewhere else — China, Singapore, UAE, wherever. They’re not going to be so shy, right?

ZIMMER: I can certainly imagine people wanting to do that stuff regardless of the strength of the approach. Certainly, even in the early 1900s, we saw people more than willing to use ideas about inherited levels of intelligence to, for example, decide which people should be institutionalized, who should be allowed into the United States or not.

For example, Jews were considered largely to be developmentally disabled at one point, especially the Jews from Eastern Europe. We have seen that people are certainly more than eager to jump from the basic findings of DNA to all sorts of conclusions which often serve their own interests. I think we should be on guard that we not do that again.

Cowen seems to be borrowing from my review in 2018 of Zimmer’s bestseller on genetics, "She Has Her Mother’s Laugh.” I wrote:

On average, two people of the same racial group are about as genetically similar to each other compared to the rest of the world as an uncle and nephew are to each other versus the rest of their racial group.

As you’ve noticed, there is both genetic diversity and similarity within families. For example, the author tends to portray his brother as possessing quite a different personality from him, which no doubt he does in many ways. Yet, in other fashions, the two brothers aren’t really all that different: Carl Zimmer is a genetics journalist for The New York Times, and his brother Ben Zimmer is a linguistics journalist for The Wall Street Journal.

Half full and half empty, heredity and environment, nature and nurture, similarity and diversity, lumping and splitting, absolute and relative … These concepts may seem like warring dichotomies that can’t be reconciled, but they are better understood as useful complements.

As F. Scott Fitzgerald said, “… the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”

That said, what about Tyler’s idea that colleges should demand aplicants’ DNA data? At present, how much would DNA add to the accuracy of the college admission process over high school GPA and SAT/ACT score?

My guess is: not all that much.

Today, we have the most data for creating polygenic scores not for IQ but for educational attainment, which is presumably affected both by nature and nurture (e.g., do your parents have enough money to pay for four years of college?). That's because we have huge sample sizes for self-designated educational attainment (as much as 3 million), but much smaller sample sizes for IQ (because taking an IQ test requires much more effort than checking an educational attainment box).

And yet the predictive ability of DNA for educational attainment is still not huge.

We aren't very far into the GWAS era, so I presume the predictive power will go up over time. (Then again, maybe it won’t.) But at present, we've already got pretty good measures of the intelligence and work ethic of college applicants.

So how much would we need DNA?

I would guess that DNA would instead be most useful for arranged marriages in Asia.

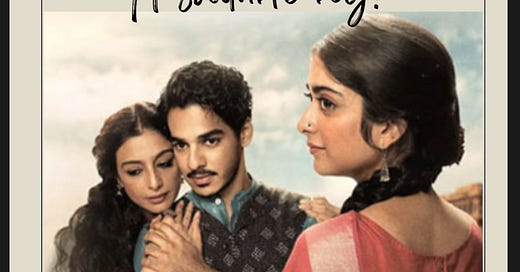

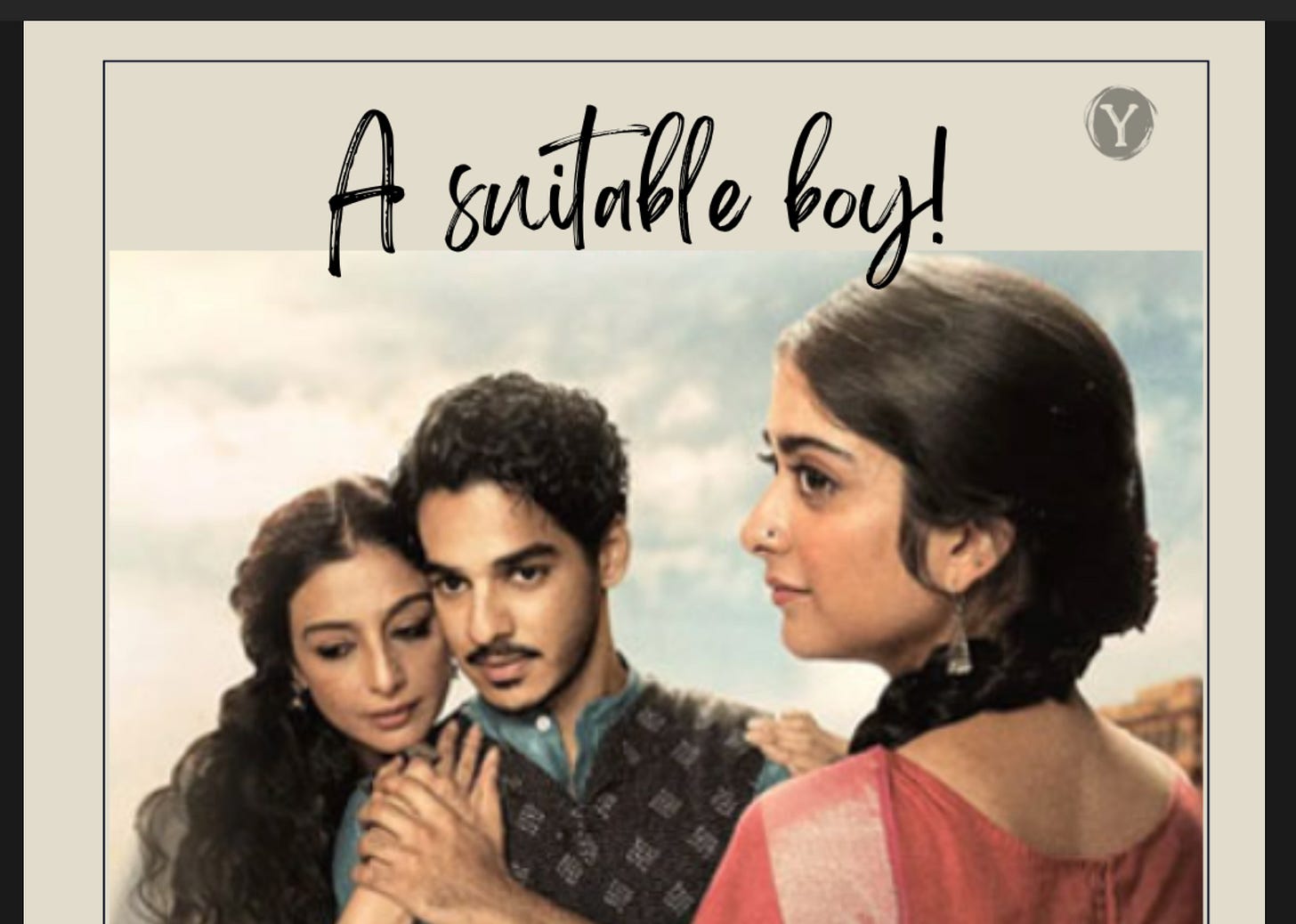

Consider our daughter’s three suitors, Kabir, Haresh, and Amit. All three appear to be suitable boys, all having graduated from colleges that require test scores at least at the 95th percentile, and all are now in remunerative professions. But which one would likely father the brightest grandchildren for us?

Somewhat counterintuitively, among three potential sons-in-law who appear to have the same IQ, the existence of regression toward the mean implies that to maximize the odds of high IQ grandchildren, you’d prefer the suitor who is the biggest underachiever relative to his ancestors, the one who is a disappointment to his brilliant parents rather than the one who is the pride of his dull family.

Once again you don’t really need DNA to figure this out: you can just meet the parents and get quite a ways toward that. But I can imagine Asian parents in the near future demanding DNA tests to see if the suitor with a 95th percentile IQ just got an unlucky mix of his fine genes, or he got a lucky mix and will likely stick our grandchildren with a mediocre mix.

Has anybody ever calculated the odds?

COWEN: But it’s not totally different. Your whole family’s super tall. If I worked for Yale Athletics, knew nothing about you, and I knew about the rest of your family, I’d be more inclined to travel to your town to scout you for the basketball team, and that would’ve been a good decision. Again, only on average, but just basic statistics implies that.

ZIMMER: You’re very kind, but what do you mean by tall? I’d like to think I’m pretty good at looking over other people's heads in a standing-room-only crowd. And the inseam of my pants is 38"; my shirt size is 18-38. But I remember in college trying out for the volleyball team and being like, “I’m done,” and then watching other freshmen spike the ball better than me.

COWEN: [Followup question]

ZIMMER: I remember what happened to Nicolas Wade in 2014, after he published "A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History." Don't cancel me!

COWEN: [Followup question]

ZIMMER: Don't cancel me!

Embarrassing.

> in the early 1900s, we saw people more than willing to use ideas about inherited levels of intelligence to, for example, decide which people should be institutionalized

This is such a common rhetorical attack. And it is so good. And also so nefarious and so false. Why? Because it assumes that we are not currently using unfair selection methods (Anti-White anti-male anti-conservative). It assumes that our current selection methods are fair and any change might be unfair