Sly & the Family Stone vs. Led Zeppelin

The Washington Post celebrates black genius while lamenting the ease of creating white generational wealth.

The first ever Top 40 singles I bought myself in 1969-1970 included Neil Young’s “Cinnamon Girl,” The Beatles “Hey Jude / Revolution,” Sly & the Family Stone’s “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) backed with “Everyday People,”

(Granted, “Everyday People” is kind of childish, but I was age 10)

and, if I recall correctly, Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song.”

Lately, there are documentaries out about Led Zeppelin and Sly Stone, which I haven’t seen:

The Zeppelin documentary is authorized. The three survivors chose to have it devoted to their triumphant first year together of 1969 when they released two landmark albums, so the tale is a happy one devoted to their music rather than to their later self-inflicted troubles.

The movie about Sly Stone by Questlove devotes attention both to his spectacular rise and then to his decades in the wilderness after he ruined his short but brilliant career with drugs and subsequently squandered countless attempts by his many admirers to help him out.

In a Washington Post review of the two documentaries, a black studies professor expresses comic heapings of anti-white animus and black ethnonarcissism. Like I’ve been saying, in the front of the newspaper, the Racial Reckoning has been memoryholed for being bad for the Democrats, but in the back of the paper, nobody seems to have gotten through to the culture writers that it’s not June 2020 anymore and racist anti-white hate isn’t the fashion of the hour.

Sly Stone, Led Zeppelin and two rock docs that treat ‘genius’ very differently

In “Sly Lives!” and “Becoming Led Zeppelin,” the divergent expectations faced by White and Black musical legends become apparent.

March 5, 2025 at 10:15 a.m.

Guest column by Emily Lordi

Emily Lordi is a mostly white-looking but apparently black-identifying English professor at Vanderbilt who writes mostly about black musicians.

“I hate to say it,” the rhythm and blues singer D’Angelo ventures toward the end of Questlove’s new documentary “Sly Lives!” (streaming on Hulu), “but these White rock-and-rollers, these motherf---ers go out in style, they go out paid. … They die in their tomato garden with their grandson, laughing

… generational wealth passed down.”

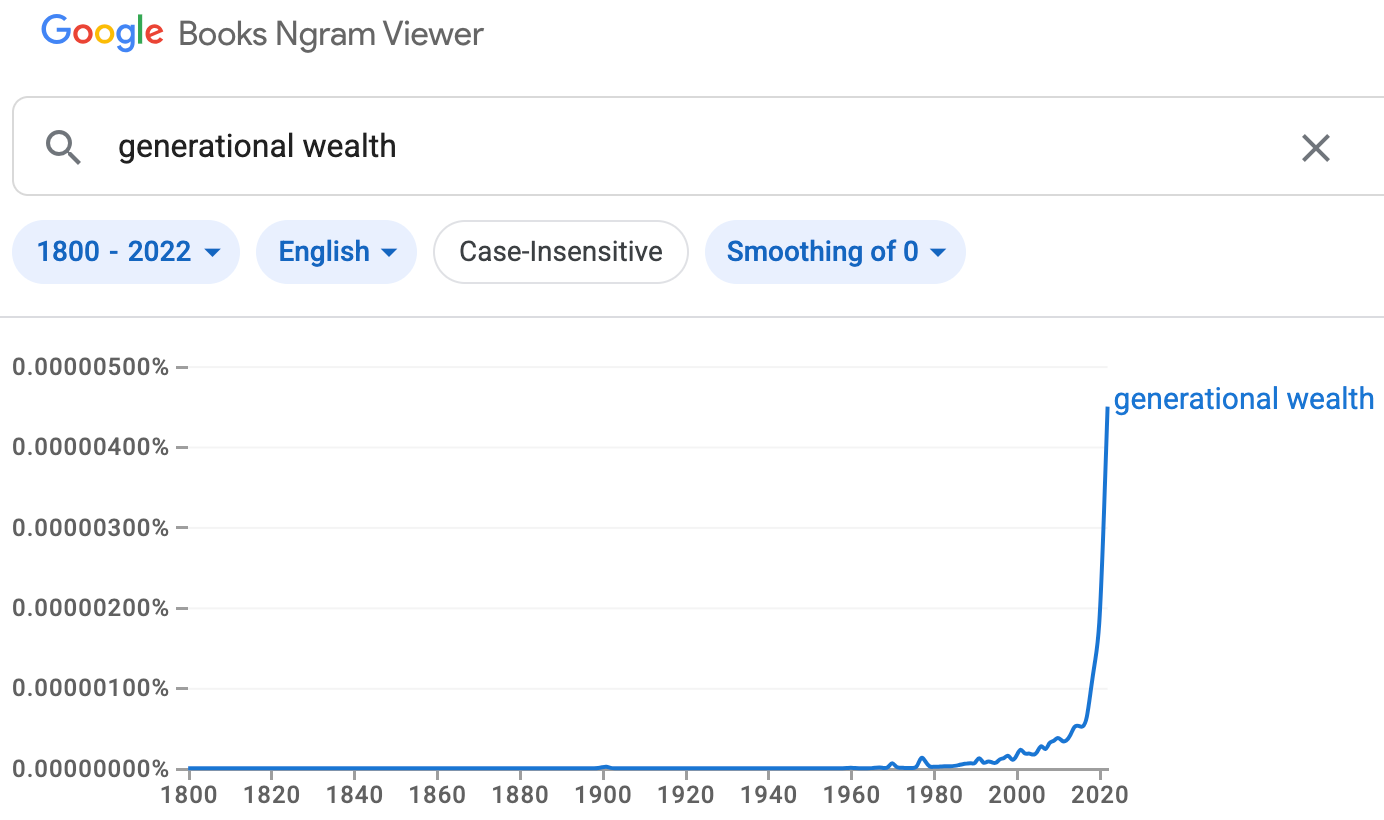

When did black intellectuals start obsessing over “generational wealth”? I would have guessed after 2008, perhaps during Occupy Wall Street, but instead the phrase didn’t really take off until 2017 during the Great Awokening.

Stone’s legacy is different. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the West Coast polymath synthesized acid rock and funk through his multiracial, mixed-gender group Sly and the Family Stone, embodying countercultural possibility. (“We got to live together!” they sang in 1968’s “Everyday People.”)

He then rescinded that optimism on his 1971 masterpiece, “There’s a Riot Goin’ On,” an album whose jagged distortions seemed to reflect the despondency of the Nixon years. Though it wasn’t the last Family Stone record, it has been heralded as the final salute of a tragic, carnivalesque figure who created some of his era’s most memorable music, only to blow his money on drugs, alienate his bandmates and withdraw from public life in the 1980s. …

But Stone couldn’t withstand what the film’s subtitle calls “The Burden of

BlackGenius.”

Or, less ethnonarcistically, Stone couldn’t withstand cocaine, which is, I am informed, a helluva drug. (Happily, it appears that Stone finally got sober in 2019 and is now enjoying a normal old age, but way too late to make music.)

Zeppelin drummer John Bonham couldn’t overcome chemical dependence, drinking himself to death in 1980. And seven years of heroin slowed guitarist/producer Jimmy Page from doing anything too groundbreaking after the mid-70s, although in the documentary he seems hale in his early 80s. In the mid-1990s, he reteamed with Robert Plant in a magnificently Orientalist version of “Kashmir” with an Egyptian orchestra:

Plant enjoyed a long, quite respectable post-Zeppelin career, doing unexpected things like teaming up successfully with bluegrass singer Allison Krauss in 2007.

But, unlike with Sly Stone, with Zeppelin there’s little sense of them self-destructing before they had their say. Their body of work is obviously among the most formidable of the second half of the 20th Century.

The phrase describes the pressures that have beset Black celebrities from Billie Holiday to D’Angelo, including isolation from the community one is expected to represent (the Black Panthers ask Stone for thousands of dollars, which he refuses to give),

It’s almost as if the Black Panthers were violent ex-con thugs.

as well as the questions that, according to Reid, haunt all Black artists in America: “Who do you think you are? What you think you’re doing?”

I would suspect that most artists wonder about such matters. I would also suspect that black artists are, on the whole, less crippled by self-doubt than are white artists.

Questlove, crucially, revises Stone’s prevailing image as an unwitting culture hero and refutes a long history of excluding Black artists from the category of genius itself.

I’m not exactly sure what the English professor is trying to say here — her prose is unclear — but plenty of black musicians got called geniuses. For example, “The Genius” was a nickname used by the press for Ray Charles since the 1950s. Charlie Parker was often praised as a genius in the late 1940s, and before him, Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong.

His depiction of Stone as a socially responsive, innovative hitmaker broadens the traditional concept of the genius as a creator of “timeless” works of art that transcend the real world and the market.

Huh?

Paywall here. 1400 words after the break.

Artists aren’t timeless, they are very much the product of their times, as the entire field of art history exists to demonstrate. And young popular musicians are less timeless than any. And the pop musicians of 1965-1969 seem perhaps the least timeless of all artists because their time is so famous.

Yet because “Sly Lives!” leaves intact the romance of the tortured genius, the film inducts Stone into a rarefied club while weighing him down in the same gesture.

One hopes that Stone, on the other side of this reappraisal, might one day get the treatment enjoyed by Led Zeppelin in their own new documentary, which depicts the British quartet as secure enough in their status as rock gods to appear as real people.

And/or Led Zeppelin controls the rights to Led Zeppelin music, so they got to specify to the documentarian that if he wanted to use their music, he should focus on the useful subject of how they came to be musical masters and pass lightly over such topics as heroin and underage groupies. (It’s similar to how in the Freddie Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody, the other members of Queen, who control the music, got to designate that they be portrayed as not just straight but as fine husbands as well.)

To see Stone in this untragic light would only magnify his achievements.

But Sly Stone burning out after just three years and spending the next half century as a derelict is a tragedy. Give him five more years at the top of his game and Stone might have established his genre of black & white funk-rock as an enduring tradition the way that Led Zeppelin, in their decade, made metal a massive feature of the musical landscape that continues to this day.

Stone is said to have sold approaching ten million records, which is a lot. But Zeppelin sold at least 20 times that number. Hence, the what-might-have-been question comes up a lot more when you think about Stone than about Zeppelin.

… Yet “Becoming Led Zeppelin” (currently in theaters), an account of the band’s formative years directed by Bernard MacMahon, inadvertently underscores the difficulties of Black genius by displaying the relative ease of the White kind.

Ehhhh … more than a few white musicians have messed up their careers about as quickly as Sly Stone. For example, Donovan’s years at the top were about the same length as Stone’s, although the post-stardom Donovan has been less of a public spectacle.

Another reason Led Zeppelin’s living members are so rich is that they benefited from the services of a terrific pit bull of a business manager, Peter Grant. But it’s not as if Grant were some upper class solicitor they’d met at Eton. Instead, he’d been a former stagehand, bouncer, and professional wrestler. White musicians do probably enjoy somewhat better management on average than black musicians (e.g., whites have on average more competent relatives), but it’s clear that Led Zeppelin got lucky in finding the innovative, ruthless, highly loyal, and apparently honest Grant.

In contrast, lots of white musicians, from Elvis on down, have gotten ripped off by their managers.

From high-backed chairs in a space that resembles a cozy British library, Zeppelin’s three surviving members — guitarist Jimmy Page, singer Robert Plant and bassist John Paul Jones — describe themselves as emboldened by a spirit of postwar optimism to seek more creatively fulfilling jobs than their parents.

Likewise, the upwardly mobile Sly Stone, whose parents were from Jim Crow Texas, grew up middle class in highly diverse Vallejo in Northern California. He was recognized as a musical prodigy by age seven. In high school, he sang in a doo-wop band that was all white except for him and a Filipino friend. He quickly found employment in the radio and music business in the San Francisco Bay area, working with both whites and blacks during the Grateful Dead-Jefferson Airplane hippie era.

Stone’s music clearly benefited from being exposed to a famously creative white culture at its Summer of Love peak.

Inspired by the “R&B boom” that Plant calls his “musical bloodstream,” they cut a demo in London and sign with Atlantic Records in New York. …

The marketplace is one of many worldly concerns the band appears to transcend. (Atlantic paid a then-massive $200,000 to sign them.)

Page had been lead guitarist of the Yardbirds, following Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, which is kind of like being the San Francisco 49ers quarterback after Joe Montana and Steve Young. And he was one of the busiest studio musicians in London. So he was a proven veteran at age 24. That $200,000 investment proved massively profitable.

Stone and Page, who were born a year apart during WWII (yet more extremely loud members of the so-called Silent Generation), enjoyed about as similar of an early trajectory as you can expect of guys of different races living 6,000 miles.

Another is the status of the blues as intellectual property.

Oh, boy …

In recent decades, black intellectuals have increasingly come to assume that all whites should send all blacks mailbox money for the benefits they’ve derived from “the culture.”

The group notoriously cribbed lyrics straight from the blues (“shake for me, girl, I wanna be your backdoor man” in the song “Whole Lotta Love”). They later settled with Howlin’ Wolf and Willie Dixon for copyright infringement.

Here’s Willie Dixon’s “You Need Love:”

and here “Whole Lotta Love” (shorter version without the nonsense in the middle):

Page was one of the all-time great recording studio masters, while the old time Delta and Chicago blues musicians ranged from inept to ho-hum in the studio.

… No one [in the documentary] pressures Zeppelin to speak to social issues, or to conform to the tastes of American critics who heard their early efforts as self-indulgent and repetitive.

That doesn’t mean they weren’t.

Critics didn’t like Zeppelin because nobody needed critics to explain a theory for why you should like Zeppelin: the 15 year olds of America immediately got this crazy Wagnerian blues juggernaut from the opening two chords of the great “Good Times, Bad Times.”

MacMahon’s decision to entrust the story to the music and musicians leaves plenty of room for nostalgia and protective obfuscation: the very stuff of myth. But it also shows the band to be as blithely charming and shrewd as real people — the thing missing from Stone’s depiction in Questlove’s documentary. …

Just maybe, Sly isn’t charming and shrewd?

Look, I understand that it’s embarrassing for a black supremacist that a lot of great 20th Century popular black musicians screwed up like Sly did. But so did lots of white popular musicians: e.g., Charlie Parker (dead at 35) vs. Bix Beiderbecke (dead at 28); Prince vs. Tom Petty (both enjoyed long careers but died somewhat prematurely around the same age of roughly the same drug); Sly Stone vs. Donovan (both are still alive, but neither has had a hit in almost 55 years).

Sure, blacks tend to screw up more than whites, but black pop musicians tend to be credits to their race while white pop musicians tend to be the blacker whites. (Granted, some musicians survive a long time through simple superiority of genes. Perhaps some of my younger readers will live long enough to be informed of a headline via NeuralLink: “With the passing of Sister Juanita Benitez, a Carmelite nun who has died at age 119, the title of World’s Oldest Human passes to Keith Richards.”)

Stone’s brand of Black genius produced tremendously influential, virtuosic, consciousness-raising hits. That contribution so far exceeds what is asked of White artists that we might stop lamenting its transience. …

After all, whoever heard of a white musical genius?

The funny thing is that the Washintgon Post reviewer’s wish that Sly Lives! had been focused only on the happy upward part of Stone’s career like Becoming Led Zeppelin is focused on good times, not bad times is not an unreasonable one — after all, we are interested in Zeppelin and Stone not because they messed themselves up with drugs and alcohol (quickly in Stone’s case, more slowly in Zeppelin’s), but because they initially made themselves into remarkably innovative musicians. We’ve all seen Behind the Music documentaries about bands screwing up. But the black lady professor’s racism is so pervasive that she just can’t keep herself from ranting.

And even in 2025, the Washington Post editors aren’t going to notice her hate.

The big victim of the racial reckoning was the black public image. They gave up cool in favor of this completely contemptible sour grapes.

Steve: You may have misremembered the Sly & the Family Stone single you bought in either late 1969 or early 1970. (I bought it then, and I'm a few years younger than you.) The B-side was "Everybody is a Star," not "Everyday People," which came out in 1968 and was Sly's first number one single. "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)" was the second; 1971's "Family Affair" was the third and last #1.

It's possible that Epic reissued the two #1 hits as a two-sided 45 in the "Memory Lane" series -- blue background with yellow floral accents -- but that would have been later in the 1970's or even the 1980's. The single you and I bought had the yellow Epic label with the "Epic" logo in a black dotted oval.

Overall, a great post: Sly Stone was prodigiously talented -- he could sing, write songs, lead a hot band, play virtually any instrument and operate a recording studio. Sort of like Prince, except that Prince was also a virtuoso guitarist and could write perfect pop songs for other artists. He was a unique talent, combining Little Richard, Jimi Hendrix and Sly with the songwriting chops of the great Motown hit factories, like Holland/Dozier/Holland, Norman Whitfield/Barrett Strong or Smokey Robinson.

The new documentaries aside, why would anyone juxtapose Sly Stone and Led Zeppelin? A better comparable for Sly is the other great rock act to come out of the Bay Area in the late '60's: Creedence. Each was tremendously successful for a few years before the wheels fell off. For Creedence, it wasn't drugs, but a combination of an insane work schedule (six studio albums in three years, 1968-70) and infighting generated by the disparity of talent between John Fogerty, the band's singer, songwriter, guitarist and producer, and the other three members. In Fogerty's next venture under the name of the Blue Ridge Rangers, he played every instrument, overdubbed all vocals (kind of like Todd Rundgren) and effectively made an album all by himself.

You make an excellent point about the importance of sound management. Peter Grant did a great job for Zeppelin, at least until the coke got to him. He personally meted out punishment to bootleg album sellers, and shielded the band from the press, concert promoters and, most importantly, anxious record executives. (Zep's contract with Atlantic gave the group full control over every aspect of its records, including the cover art: even the artist-friendly Ahmet Ertegun was dismayed by the cover of the untitled fourth album, the one now known variously as "Led Zep IV," "Zoso," and "the one with 'Stairway to Heaven.'" But Peter Grant, acting on Jimmy Page's instructions, put his foot down, insisting on an album cover with no picture of the band, no title, nothing to identify it as Led Zeppelin's newest LP. Somehow, fans figured it out.)