The Curse of Toumaï

A superb new article about human paleontology can help us get a smarter perspective on whether race is a scientific concept or not.

Educated 21st Century people tend to assume that race isn’t scientific because they hold a view of science derived mostly from physics. Science, in the conventional wisdom, must provide answers that are clear-cut, certain, authoritative, inarguable, with no room for differing opinions. If categories are less than utterly hard-edged, then they can’t be Scientific.

Of course, even physics isn’t really like that.

And all the sciences related to biology or the human world (e.g., linguistics) are thoroughly beset with inevitable lumper-splitter controversies about how best to carve nature at the joints.

A good example of this messiness is paleontology, the study of old bones and fossils, especially its glamor subfield, the study of ancient human remains.

Despite its use of calipers, those instruments of the devil, paleoanthropology is not a controversial field in the public’s mind. Building speculative family trees of ancient kin of modern humans based on a handful of old bones is not fatally tainted by racism in the view of the conventional wisdom.

Instead, it’s The Science!

But behind the scenes in human paleontology … well … there’s little but controversy, as vividly described in a wonderful new long form article in The Guardian by Scott Sayare. His tale could be, in plot if not prose style, a Nabokov satire on egomaniacal college professors. (It’s far above the usual quality of Guardian articles.)

A century and a half ago, the scientific dispute that has been festering since 2001 over whether a six or seven million year old skull found in Chad is the oldest known hominin (kin of modern humans) or merely a more distant hominid (kin of today’s great apes, which include us) might well have led to one or more duels being fought.

The curse of Toumaï: an ancient skull, a disputed femur and a bitter feud over humanity’s origins

When fossilised remains were discovered in the Djurab desert in 2001, they were hailed as radically rewriting the history of our species. But not everyone was convinced – and the bitter argument that followed has consumed the lives of scholars ever since

By Scott Sayare

Tue 27 May 2025 00.00 EDT

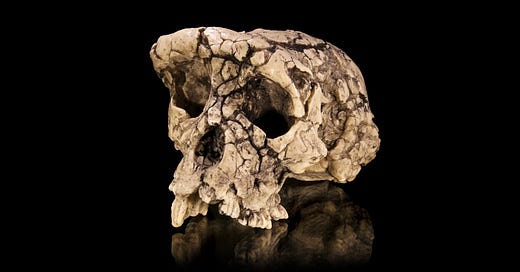

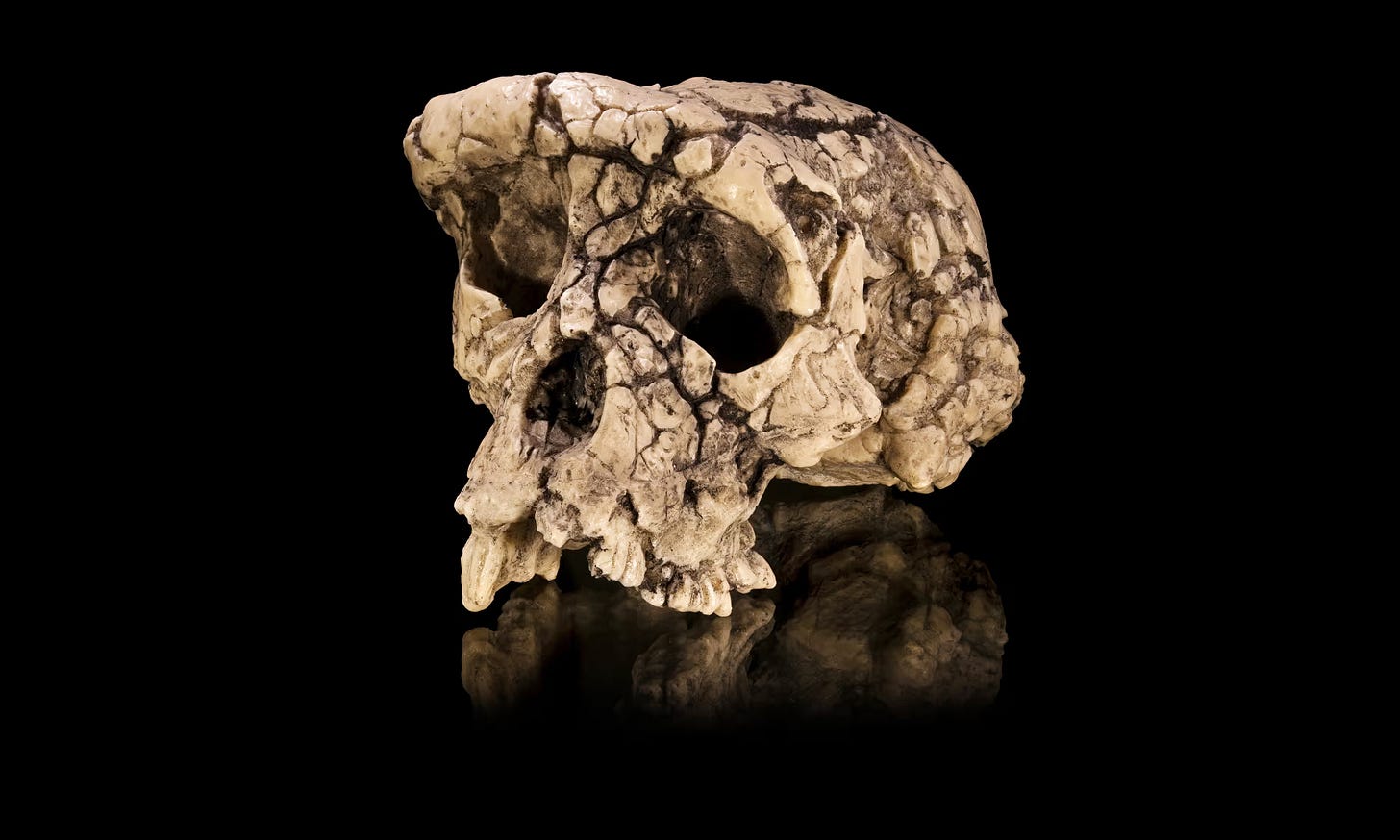

On a late-summer day in 2001, at the University of Poitiers in west-central France, the palaeontologist Michel Brunet summoned his colleagues into a classroom to examine an unusual skull. Brunet had just returned from Chad, and brought with him an extremely ancient cranium. It had been distorted by the aeons spent beneath what is now the Djurab desert; a crust of black mineral deposits left it looking charred and slightly malevolent. It sat on a table. “What is this thing?” Brunet wondered aloud.

He was behaving a bit theatrically, the professor Roberto Macchiarelli recalled not long ago. Brunet was a devoted teacher and scientist, then 61, but his competitive impulses were also known to be immoderate, and he seemed to take a ruthless pleasure in the jealousy of his peers. “Michel is a dominant male,” Macchiarelli told me. “He’s a silverback gorilla.”

Inspecting the skull, one could make out a mosaic of features at once distinctly apelike and distinctly human: a small braincase and prominent brow ridge, but also what seemed to be a rather unprotruding jaw, smallish canines and a foramen magnum – the hole at the base of the skull through which the spinal cord connects to the brain – that suggested the possibility of an upright bearing, a two-legged gait. Macchiarelli told Brunet he did not know what to make of it. “Right answer!” Brunet said.

The discovery was announced to the world the following year on the cover of Nature, the leading scientific journal, and in a televised ceremony in the Chadian capital, N’Djamena. “A new hominid is born,” Brunet declared. “By virtue of his age, he is the ancestor of all Chadians. But also the ancestor of the whole of humankind!”

The skull, which Brunet called “Toumaï” – a name from the Djurab, meaning “hope of life” – belonged to a two-legged animal of the Upper Miocene epoch, between 6 and 7m years old. Assuming it was indeed our distant forebear, it was the most ancient ever found, by a margin of as much as 1m years. …

Brunet, to whom the honour of naming the new species fell, called it Sahelanthropus tchadensis: “Sahel Man of Chad.”

Paleontology sometimes has disputes about whether a new fossil represents a new, as of yet unknown species (or, even better, a new genus), or is just another example of an already known species. It’s more professionally glamorous to be acknowledged as discovering a new species (much less a genus), so paleontologists tend to be splitters when it come to their own finds.

Paywall here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Steve Sailer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.