Trump Time

Would abolishing daylight saving time be a winning issue for the President-Elect?

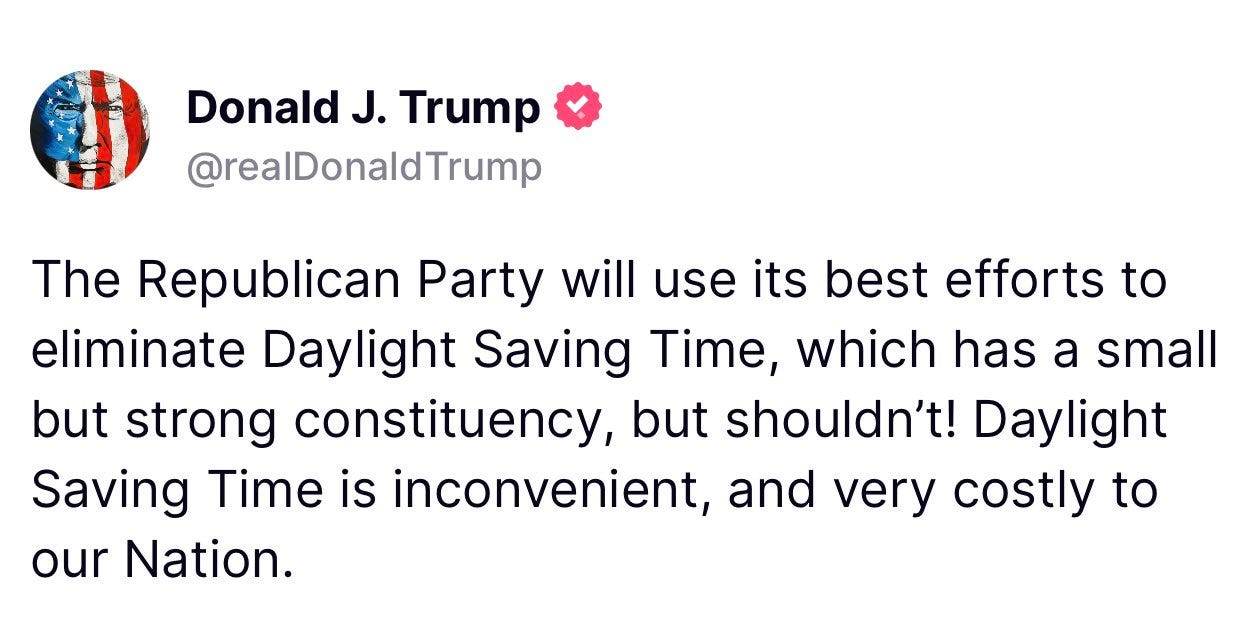

Daylight saving time is back in the news because Trump came out against it on Friday.

Clock policy has been an interesting political science case study because it has been a rare contentious yet non-partisan, non-identity, and non-regional issue in the 21st Century in a time when everything else tends to turn into a red vs. blue, black vs. white, and/or urban vs. rural debate.

A lot of people have strong opinions on what time it should be, but, like Trump’s, they appear to arrive at their arguments idiosyncratically (or, often, just out of ignorance). Are you an early bird? Do you like getting up in daylight or darkness? Are you offended by messing with clocks? People seem to have all sorts of unpredictable reasons for their views.

Interestingly, time traits like being a morning person or a night person don’t seem to correlate much with other identity categories like sex and race. They seem more like left-handedness, which appears to be distributed pretty randomly, and left-handers thus aren’t a coherent identity politics bloc.

For example, when the Senate voted to go to year-round DST in 2022 (the House refused to consider it), the main sponsors were Patty Murray (D-WA) and Marco Rubio (R-FL) from opposite corners of the country.

Huh?

This issue is a natural for Trump. Despite being denounced as a far-right fascist new Hitler for nine years, he’s actually not very ideological, and time policy seems orthogonal to most ideologies. Instead, he’s egomaniacal. He’s got an opinion on clocks, so he may run with it. (Or he may just drop it. After all, there are more important things to do and, as I’ll explain below, it’s hard to put together a majority behind any single time policy. We’ll see.)

And there’s ignorance: a lot of people with strong opinions on time don’t realize that we’ve had most of the alternative policies during my lifetime and got rid of them.

Much of the country had year round standard time until clock-changing was mandated by the federal government in 1967 so we would have 6 months of daylight saving time.

The law lets states opt out of daylight saving time completely, but at present the only states that do are tropical Hawaii and sun-blasted Arizona (where the state motto should be “Hurry, sundown”).

What your state is not allowed to do is opt-in to year-round DST, or invent your own variation, like starting DST on a different date or having 45 minutes of DST or whatever: too confusing for everybody else.

Then, due to the Energy Crisis, Congress switched to year-round daylight saving time in early January 1974. This proved so unpopular that Congress got rid of it later that year and everyone in public life vowed never to speak of what they had done again — or at least it seems that way.

It’s possible that if year round DST had begun in the fall of 1973, people might have have gotten more used to the sun coming up later and later in the morning. But switching to it on the first week of school back from Christmas vacation was horrible: I can recall getting up that Monday morning in the pitch black with the rain pelting down and feeling like a kid in London in 1940 getting dressed to go to a bomb shelter during the Blitz.

After the 1974 mistake, the current system of partial daylight saving time proved popular enough that four more weeks was added in the spring in 1987. And then in 2007, another four weeks of DST was added to the spring, and one more in the fall because Big Candy thought Halloween would be even more popular if it didn’t get dark so early. So, now we have 35 weeks of DST per year (about two-thirds of the year).

So nobody on the pro-clock-changing side has anymore complaints or wishes. Hence, they aren’t very active on social media, where it’s more natural to complain than to praise the current system.

At this point, pro-partial DST lobbies like the golf industry have won so many victories that they’ve folded their tents and gone home from the fight. (I’m not sure why Trump, a golf course owner, is against DST when his peers are for it.) Nobody who is okay with clock-switching is out there anymore arguing that what we really need a few more weeks of DST, like they used to be up through 2007.

This is a funny example of how achieving your maximum demands can weaken your side in the long run. That might be more common on issues like this one that don’t have an identity politics angle. For most issues, you want to keep winning because it shows your group is powerful and should be feared. But clock policy views don’t map well to enduring groups: the trick-or-treat and golf industries really never had much in common, so it’s not surprising their coalition dissolved as soon as they won their maximal demands of 35 weeks of DST.

Similarly, individual views on daylight saving time appear to be motivated by traits like: Are you an early bird or a night owl? But these seem to be fairly randomly distributed among identity groups, so they aren’t good for forming coalitions across multiple issues.

But Trump might decide to make time change reform a big deal in his second term. Will the country respond by sorting itself into pro-Trump and anti-Trump sides, as on so much else?

Here’s the paywall: lot’s more beneath it.

From the New York Times news section:

Trump Says He Supports an End to Daylight Saving Time

President-elect Donald J. Trump said on social media that the time change is “inconvenient” and that the Republican Party would try to put an end to it.

By Hank Sanders

Dec. 14, 2024

Updated 8:25 p.m. ET

President-elect Donald J. Trump called daylight saving time “inconvenient, and very costly to our Nation” in a social media post on Friday and said the Republican Party would try to “eliminate” it, in the latest effort to end the twice-yearly time change.

Most states change their time by one hour — in March, when clocks spring forward, and in November, when clocks fall back. …

Many people called the time changes antiquated.

Why? Your most important clock, your phone, changes automatically these days.

Some noted that daylight saving time would most likely not be eliminated, as his post suggested, but rather would be made permanent, and the time changes would be eliminated.

One reason this might not turn into a pro-Trump vs. anti-Trump issue is because there are three main camps: those who more or less like the current system of changing clocks twice per year, and the two sides against changing clocks: those who favor year-round standard time and those who favor year-round daylight saving time.

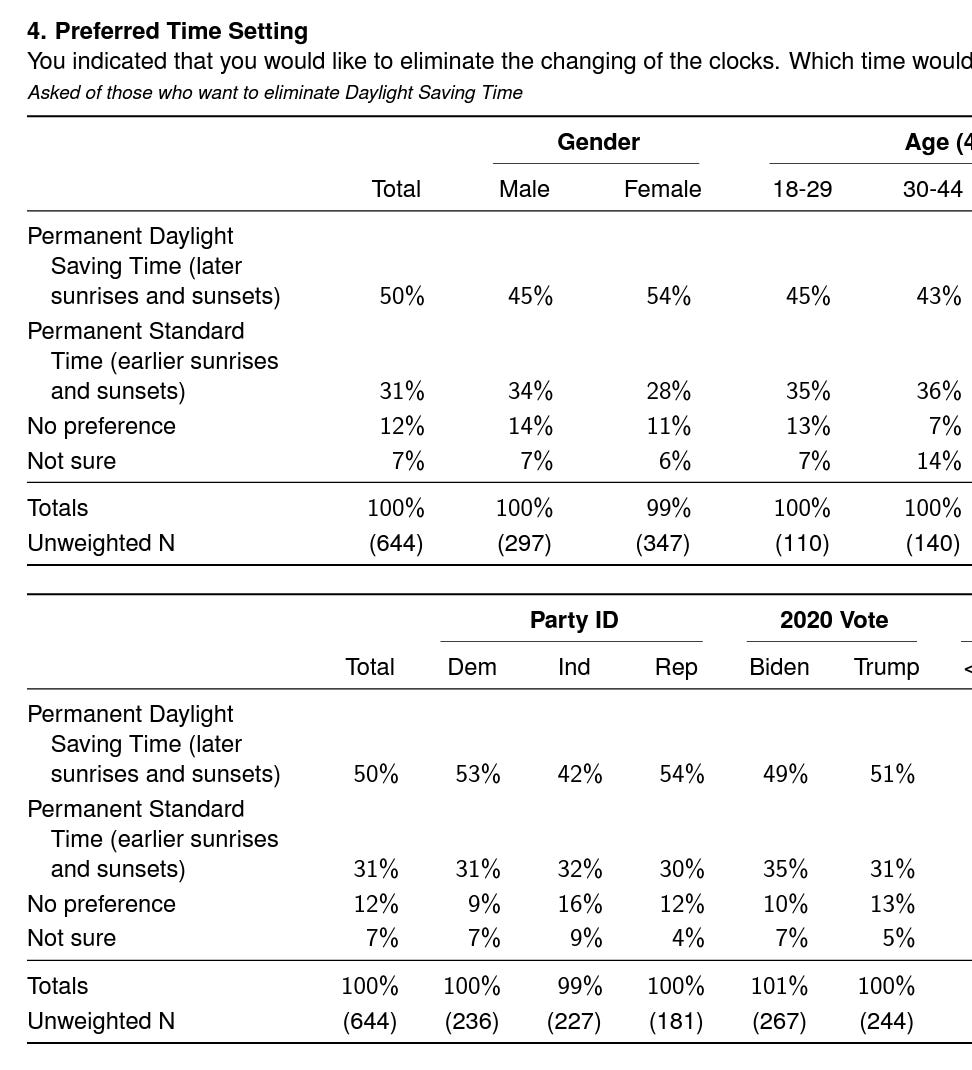

A 2023 YouGov poll of 990 Americans taken on March 6-9th (the last week of standard time in 2023), found that most Americans opposed clock-changing by a 3 to 1 ratio. (Strikingly, a majority of Americans were wrong about whether they were currently in daylight time or standard time, although the question might have been phrased poorly.) But there wasn’t strong agreement among proponents of not-changing clocks on whether to switch to permanent daylight time (50%) or permanent standard time (31%).

So, 35% want year-round DST, 22% want the current partial DST system, and 19% want year-round standard time, plus a sizable fraction are uncertain. Not enough research has been done on what voters’ second choices would be.

What’s uncertain is what kind of coalition could be assembled: are more voters who favor year-round standard time motivated because they hate changing clocks, and thus would willingly join a year-round daylight saving time coalition, or because they hate getting up in the dark and thus would prefer the current system of changing clocks to year-round DST?

So, at present it sounds like a big ball of twine with no obvious solution. And even if some political genius put together a majority, how long-term would the political payoff be? After a decade or so, the public would just forget and go back to complaining about whatever the new policy is.

Note that 2020 Trump voters (76%-15%) were slightly more in favor of eliminating clock-changing than Biden voters (66%-17%), but the difference was not large:

Similarly, among those wanting to stop changing clocks, Trump (51%-31%) and Biden voters (49-35%) were comparably split between year-round DST vs. year-round ST.

So it’s not like Trump voters are demanding one particular solution and would get to enjoy imposing a policy on the country that Biden voters hate.

What’s the fun of that?

Personally, I prefer the current system.

Let’s take Chicago as an example. Under our partial DST system, the sun comes up in Chicago on June 21 (the longest day) at 5:16 AM CDT and sets at 8:29 PM. On December 21 (the shortest day), it rises at 7:15 AM (CST) and sets at 4:23 PM.

Under year-round standard time, it would rise on June 21 at 4:16 AM (on Saturday nights in Chicago, the bars are still open until 5:00 AM Sunday, or were in my days in Chicago as a yuppie) and set at 7:29 PM. Having daylight from 4:16 to 5:16 AM is pretty useless compared to having daylight from 7:29 to 8:29 PM, which is why we have DST.

Under year-round DST, the sun would come up on December 21 at 8:15 AM and set at 5:23 PM.

But I’ve heard one guy on Twitter (unfortunately, I forgot his name) suggest a good reform to the current system: move the clock-changing moment from Sunday at 2:00 AM to Saturday at 2:00 AM. That would give you two days to adjust to losing an hour in March before Monday morning comes around.

If we do decide we can’t bear to change clocks anymore, it would seem more sensible to go to some degree of year-round DST. After all, we currently spend 2/3rds of the year on DST, due to 3 acts of Congress, so it evidently has its advantages.

But, as we saw in 1974, an hour of DST is excessive in winter.

So, if we must have year-round daylight saving time, 30 minutes of DST year-round sounds better than 60 minutes of DST year round.

The downside is that that would knock the US off of the global norm of starting hours when Greenwich Mean Time starts hours. India is a rare major country that’s 30 minutes off of GMT.

I suspect that 30 minutes of DST would be inconvenient for people who make a lot of international phone calls for business. E.g., is 10:45 AM in New York OK to call a government office in Paris that closes at 5:00 PM? (Of course, these days, you can look up the answer quickly on your phone.)

Other people have more radical suggestions, such as going back to local sun time, with noon in every town being a few minutes different from its neighbor to the east or west. But the railroads got together in Chicago after the Civil War to invent time zones to cut down on the number of head-on train crashes. Call me an extremist, call me a nut, but I remain an anti-head-on-crashite.

Conversely, others want to have a single time zone for the whole country or the whole world. But we already have Greenwich Mean Time, which is a useful complement to time zones.

The Communist Chinese have tried to have a single time zone for their entire country, which causes problems in the far west province of Sinkiang. From Wikipedia:

Xinjiang Time has been abolished and re-established multiple times, particularly during the 1970s and 1980s. In February 1986, the Chinese government approved the use of Xinjiang Time (UTC+06:00) in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (thus excluding area colonized by Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps) for civil purposes, while military, railroad, aviation, and telecommunication sectors were supposed to continue using Beijing Time (UTC+08:00). However, the decision was rejected by the local ethnic Han population and some Han-dominated regional governments.

The choice of time zone used in Xinjiang is roughly split along the ethnic divide, with most of the Han population observing Beijing Time, and most of the Uyghur population and some other ethnic groups following Xinjiang Time. Accordingly, the Xinjiang Television network schedules its Chinese channel according to Beijing Time and its Uyghur and Kazakh channels according to Xinjiang Time. In some areas, local authorities use both time standards side by side.

The coexistence of two time zones within the same region causes some confusion among the local population, especially when members of multiple ethnic groups want to communicate with each other: whenever a time is mentioned, it is necessary to explicitly state whether the time is Xinjiang Time or Beijing Time, or to convert the time according to the ethnicity of the target audience. Additionally, some ethnic Han in Xinjiang might not be aware of the existence of Xinjiang Time because of the language barrier.

So, at least, having separate ethnic times is a problem we don’t have here.

In summary, I recommend letting states opt-in to year round DST to see if there really is much support for it once people have more experience with it.

In the meantime, move clock-changing from Sunday at 2 AM to Saturday at 2 AM.

Regardless of what happens or if nothing happens, it should be declared by Executive Order as Trump Fantastic Time.

This is another case of much ado about nothing. I am 79 years old and have lived under both DST and Standard Time. I'm also a retired professional pilot and former military aircrew member and dealt with time zones on a daily basis. DST was implemented during World War II as a means of increasing production. It continued until after the Korean War. It was re-implemented in the early 70s after the Yom Kipper War and the resulting oil embargoes and has been with us ever since. It's not that big a deal. The one benefit I realized from it was when I was young and single (again) and we got another hour in the dance halls, which closed at 2 AM.