Was the first musician of the 21st Century Glenn Miller?

Yesterday, I posted some graphs I made from the database used in Madeline Hamilton’s new study of the (de-)evolution of melody in Billboard’s Top Five hits from 1950-2022. Top of the charts melodies have gotten progressively more predictable over the last three quarters of a century.

When did this trend toward simplification begin?

It’s not exactly the same as the similar trend toward repetition, but it is a related impulse. Traditionally, Western classical music is, arguably, excessively creative. When a great composer stumbled upon a hook, rather than pound it into the ground over and over for the audience to thoroughly enjoy, he typically would instantly start working variations on it.

By 1928, classical composer Maurice Ravel’s 15-minute long Bolero repeated the same notes eight times in a row with intensifying orchestration, before a small variation in the climactic ninth repetition. Here’s the much-shortened Torvill & Dean Bolero at the 1984 Winter Olympics ice dancing final:

But, in the long history of Western music, Bolero was recent enough that it remains under copyright in the United States through the upcoming New Year’s Eve before finally joining the public domain in 2025.

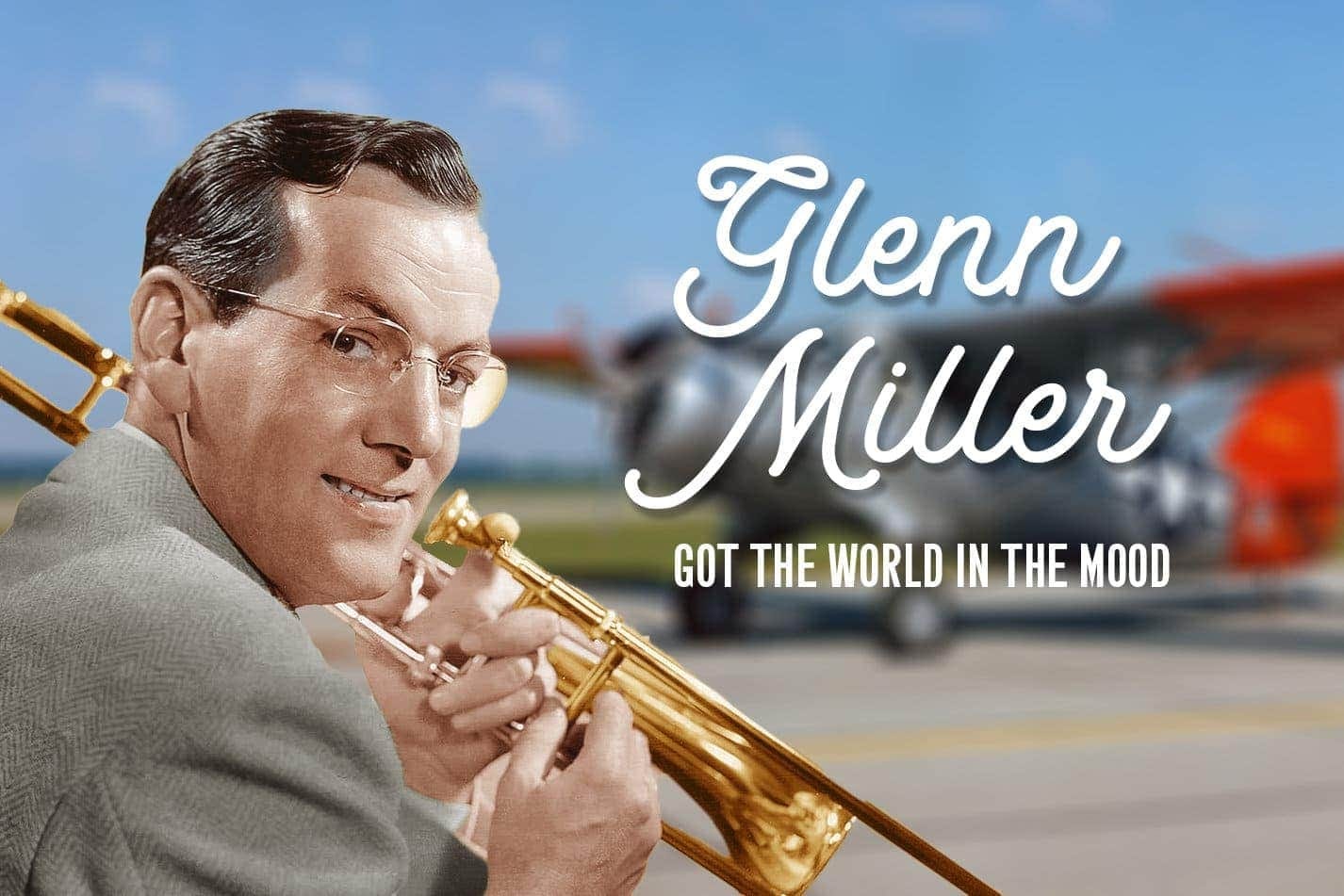

An important pop star in the shift toward giving the audience what they want without all that tiresome creativity was Glenn Miller, who in 1939 purchased the rights to a song, “In the Mood,” that other bandleaders hadn’t been able to make work. Miller and his staff restructured it into the biggest hit of the swing era.

From my book review in Taki’s Magazine of Let’s Do It: The Birth of Pop Music by Bob Stanley, a history of 20th Century popular music before rock:

Stanley gives nerdy white guy Glenn Miller, the most popular but most critically derided of big-band leaders, rightful recognition as “futurist and prescient.”

Critics and jazz historians traditionally prefer Benny Goodman’s band to Miller’s because Goodman honored jazz’s dedication to improvisation. For example, at the pinnacle of Goodman’s career, the “no drinking, no dancing” 1938 Carnegie Hall concert, Goodman gave the climactic solo of “Sing, Sing, Sing (With a Swing)” to pianist Jess Stacy (9:27 on the recording), who delivered an unexpected Debussy-like turn that became legendary when finally released in 1950.

In contrast, Miller’s massive 1939 hit “In the Mood” was engineered for dancing rather than artistry.

Stanley writes:

He made music that was, and remains, so popular that it is almost never explored by critics (the jazz critic’s default position is that it isn’t jazz, so why bother?)… He was obsessed in a scientific way with music, with how it could and should sound…. In no way was he instinctive—possibly one reason why most jazz histories pass up on him completely—but new sounds obsessed him, the most exciting, the most commercial, the most modern. Miller incorporated melodic riffs…played again and again with a rhythmic monotony, which allowed little room for soloing but gave the sound a hypnotic aspect…. Those riffs without solos, which bored jazzers, thrilled dancers and prepared them for the purely rhythmic music of the late twentieth century that began with R&B, continued through rock ‘n’ roll, and would find its purest form in house music.

In 1942, the 38-year-old Miller gave up a $20,000 per week income to become a U.S. Army officer. Stationed in London in 1944, Miller’s commanding officer, movie star David Niven, ordered Miller’s orchestra to recently liberated Paris to give a Christmas day radio concert. To get to Paris early, Miller hitched a ride on an unofficial flight, which went down in the English Channel on December 15, 1944.

Complex things take intelligence and diligence to appreciate. Modern education doesn't nuture the habits required for many to do this. With popular music the death of the album accelerated this. Listening to an entire album often exposed one to songs that weren't necessarily one's favorites but often with multiple listenings one came to appreciate. Modern media allows us to easily go for the quick high and narrow the range of listening opportunities.

Somewhere in the numbers here I sense the effects of the Industrial Revolution, nation by nation, and the concomitant change in life tempo and the assembly line production idea.