What should be done about college admissions?

Colleges have gotten worse at identifying the best applicants since 1995. This wouldn't be hard to fix.

Besides being April Fools’ Day, April 1st is the the day when we hear from all the high school seniors with 1590 SAT scores and 4.37 GPAs who got rejected by all 27 colleges they applied to, from MIT to Wayne State.

One obvious problem is that it has become harder for kids to stand out just because they are smart and hard-working.

In this post, I’m not going to delve into the deeper questions about whether America should have a pyramidical system of colleges ranked by prestige, largely driven by endowment size, with H-Y-P-S at the top. After all, Canadians don’t worry much about which college they go to, and Canada seems like an OK country Canada delenda est!

Instead, I’m just going to focus on some simple reforms that could make the current system work better at identifying the highest potential applicants, the way it did in the later 20th Century.

There are several main reasons for this worsening failure of college admissions to find the academically best applicants.

First: because of increases in the number of applicants, both nominal and real.

Nominal: The introduction of the online Common App made it much easier to apply to numerous colleges, so it’s not uncommon to see students apply to a dozen or two dozen colleges now.

Real: Today there are far more applicants to elite U.S. colleges from overseas, and the big increase in Asians in America has helped change the culture toward making more Americans want to get into famous colleges.

Second, the number of people getting in for non-academic reasons probably went up.

For example, colleges have long favored jocks, both in the revenue sports like football and basketball, and in non-revenue sports like squash. The latter appears to be because elite colleges’ minor sport athletes tend to go into finance and other well-paid careers, make a lot of money, and some of them are quite generous toward the old school.

Now, though, colleges have to have roughly as many female as male athletes. I doubt if women athletes write as many big checks to the old school as male athletes do on average (women tend to be more practical and less nostalgic than men). But are admissions’ departments allowed to take that into consideration and not give as much extra credit to women athletes?

I don’t know. The relationship between who is likely to donate and who is likely to get admitted is something that colleges have no doubt studied intensely, but they have also kept their findings under wraps. I’ve been asking about it for years, but I’ve never seen a Raj Chetty-style paper on the subject spilling the beans.

Also, affirmative action got inflated during the Great Awokening, with ultra schools going from about 8% black to 14% black.

And there wasn’t much evidence as of 2024 that colleges other than MIT were taking the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision seriously. We’ll see late this year if elite colleges feel like they ought to obey the Supreme Court on their second try.

MIT’s 2023 freshman class, for instance, was 15% black, which is obviously ridiculous, when if MIT wasn’t using affirmative action, its freshman class would likely be around 1% black. But then after the Supreme Court’s abolition of racial preferences in the summer of 2023, MIT reduced its black share to a more reasonable compromise of 5% in 2024. In contrast, Harvard’s black share in 2023 was 14%. Then, after the Supreme Court decision, Harvard announced that they had chanced their methodology so they instead let in 18% blacks in 2023 but only 14% in 2024.

Finally, the inputs into college admissions decisions, such as high school GPA and test scores, have gotten highly inflated over the years.

At the lower end, there’s been a big push to flunk out fewer high school kids. The National Center for Education Statistics reports:

In school year 2021–22, the U.S. average adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR) for public high school students was 87 percent, 7 percentage points higher than a decade earlier.

So, the flunkout/dropout rate went down from 20% to 13% in a decade.

Giving fewer F’s at the bottom means giving fewer B’s and more A’s near the top.

Also, many high schools have informally switched from an A/B/C/D/F grading scale to an A/A-/B+/B/C grading scale.

At the top, there has been a big expansion in taking Advanced Placement courses in high school, which award an extra GPA point (e.g., a B in the course counts as a 4 rather than a 3 for GPA, and an A counts as 5 rather than a 4), although a University of California study found that only awarding a half of GPA point would better predict college performance.

The most self-destructive step taken by colleges was of course going to test-optional (or, in the case of the University of California, test-forbidden) during covid/George Floyd. That’s going away, with MIT in the lead, but not fully yet. The U. of California still forbids students from sending in test scores.

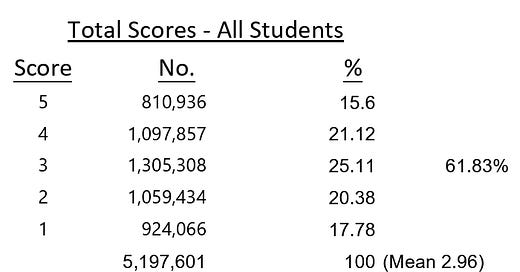

SAT and ACT tests have considerably inflated their scores as well. Back in 1991, only nine students in the country got a perfect 1600 on the SAT. Current estimates are in the 500+ range for perfect scores on the SAT and several thousand annually for a perfect 36 on the ACt.

Also, more students take the tests multiple times and/or take both the SAT and ACT. (Only the highest score counts.)

And test prep has gotten much more intensive as Tiger Mothers flock in from parts of the world that have been engaging in intensive test prep for millennia.

Here are some fixes for high end college admissions:

Paywall here:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Steve Sailer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.