Why are so many movies with no lines for women classics?

A 2016 study of 2,000 film screenplays found men get about 80% of the dialogue. Among the 100% male movies are quite a few all-time greats.

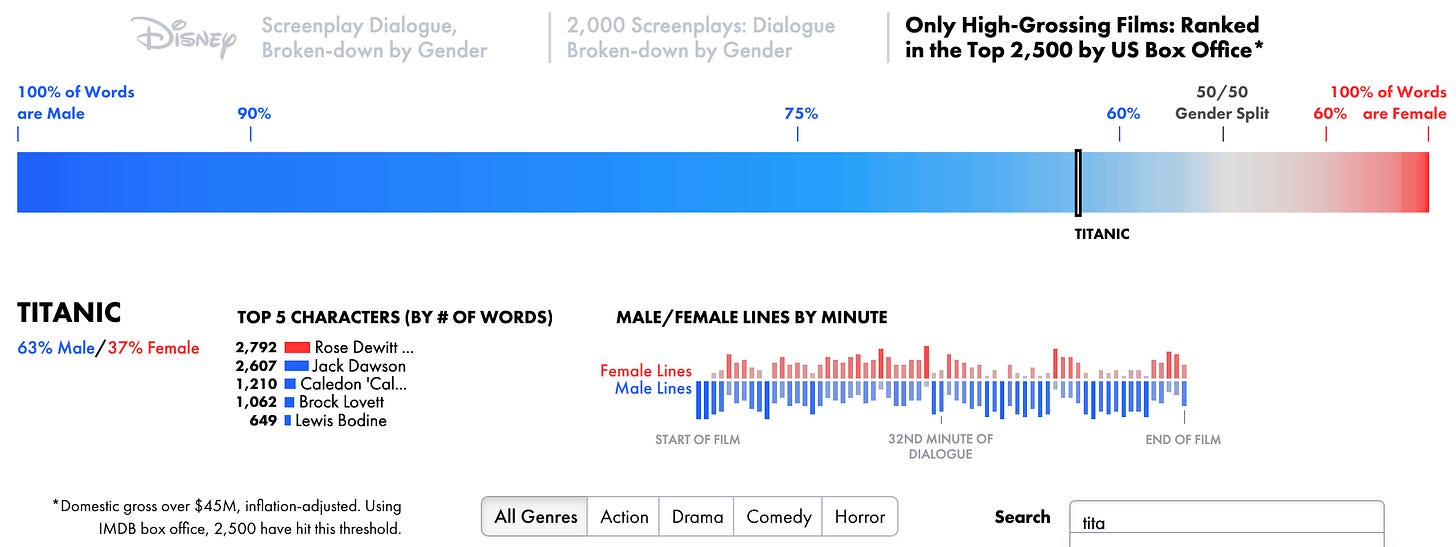

Back in 2016, a website called Pudding published an impressive study by Matthew Daniels of 2,000 movie screenplays going back to the 1980s by how many words are spoken by male vs. female characters:

Film Dialogue from 2,000 screenplays,

Broken Down by Gender and AgeLately, Hollywood has been taking so much shit for rampant sexism and racism. The prevailing theme: white men dominate movie roles.

But it’s all rhetoric and no data, which gets us nowhere in terms of having an informed discussion. How many movies are actually about men? What changes by genre, era, or box-office revenue? What circumstances generate more diversity?

We didn’t set out trying to prove anything, but rather compile real data. We framed it as a census rather than a study. So we Googled our way to 8,000 screenplays and matched each character’s lines to an actor. From there, we compiled the number of words spoken by male and female characters across roughly 2,000 films, arguably the largest undertaking of script analysis, ever. …

This appears to be an Availability Sample of everything Daniels could get his hands on and then work conveniently with. But that seems more or less okay.

Methodology

For each screenplay, we mapped characters with at least 100 words of dialogue to a person’s IMDB page (which identifies people as an actor or actress). We did this because minor characters are poorly labeled on IMDB pages. This has unintended consequences: Schindler’s List, for example, has women with lines, just not over this threshold. Which means a more accurate result would be 99.5% male dialogue instead of our result of 100%. There are other problems with this approach as well: films change quite a bit from script to screen. Directors cut lines. They cut characters. They add characters. They change character names. They cast a different gender for a character. We believe the results are still directionally accurate, but individual films will definitely have errors.

Each screenplay has at least 90% of its lines categorized by gender. If you notice a missing character from the analysis, their lines may be in the remaining 10%. If a character was cut from the film but is present in the screenplay, we inferred his or her gender based on the script’s pronouns.

Across thousands of films in our dataset, it was hard to find a subset that didn’t over-index male. Even romantic comedies have dialogue that is, on average, 58% male. For example, Pretty Woman and 10 Things I Hate About You both have lead women (i.e., characters with the most amount of dialogue). But the overall dialogue for both films is 52% male, due to the number of male supporting characters….

How many screenplays have women as lead characters?

In 22% of our films, actresses had the most amount of dialogue (i.e., they were the lead). Women are more likely to be in the second place for most amount of dialogue, which occurs in 34% of films. The most abysmal stat is when women occupy at least 2 of the top 3 roles in a film, which occurs in 18% of our films. That same scenario for men occurs in about 82% of films.

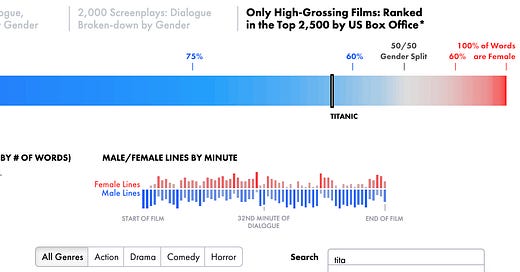

After all, what woman has ever wanted to see a movie, such as Casablanca, in which the heroine has to choose between two dynamic men? A few women went to see Titanic, I’ve heard, but Kate Winslet’s Rose and the other women only gets 37% of the dialog among the major characters:

Men also tend to play a much larger percentage of villain and comic relief roles in movies.

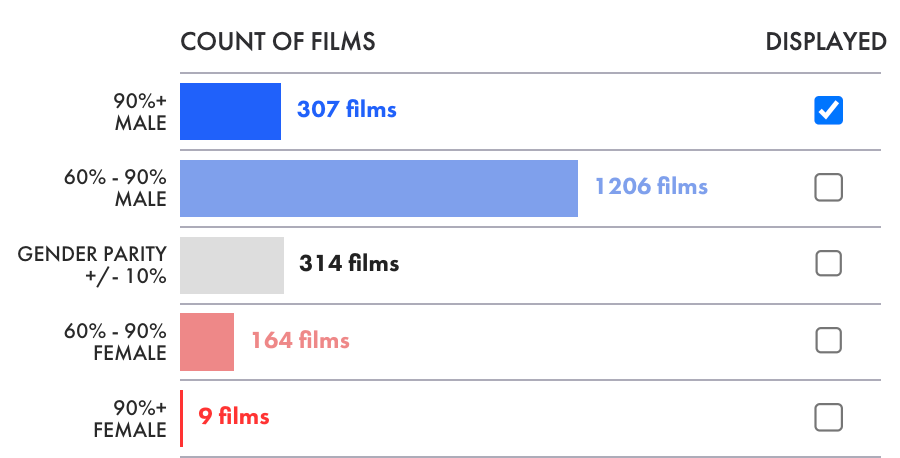

Oddly, the article doesn’t offer a summary statistic such as that men get 80% (or whatever the figure is, but it looks to be somewhere around 80%) of the dialogue in movies. But it’s definitely way up there:

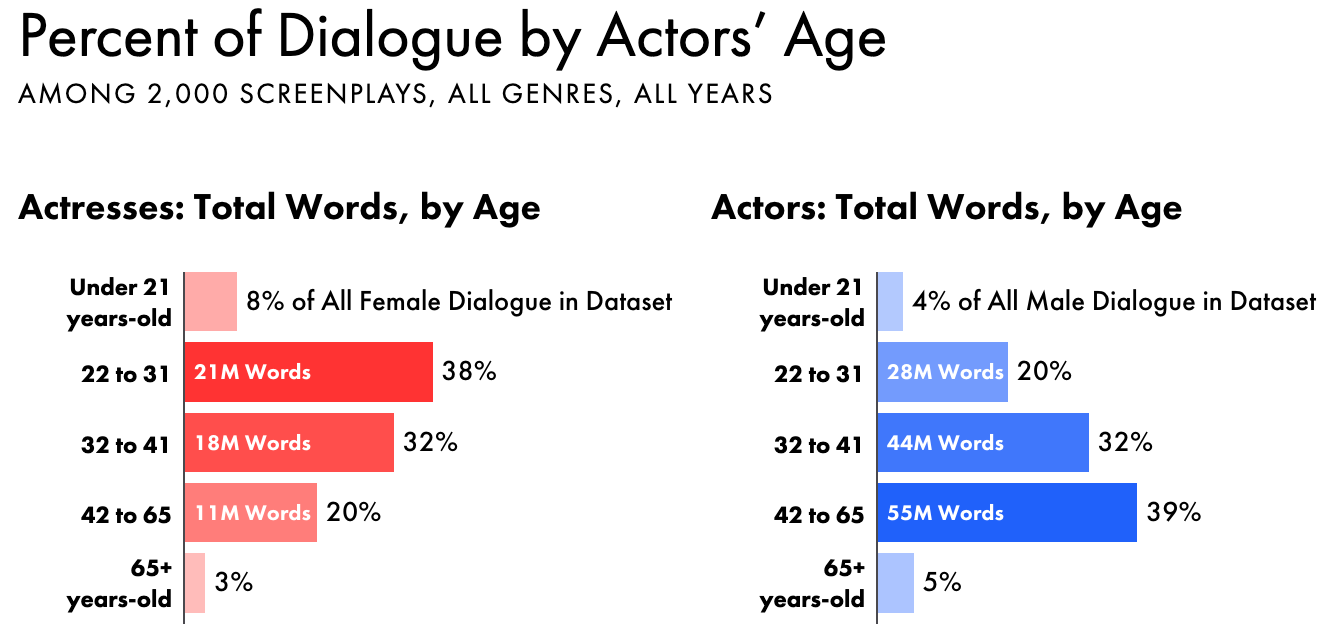

Not surprisingly, movie actors tend to be older than movie actresses. Actors get their most lines between age 42 and 65, while actresses get their most lines between 22 and 31:

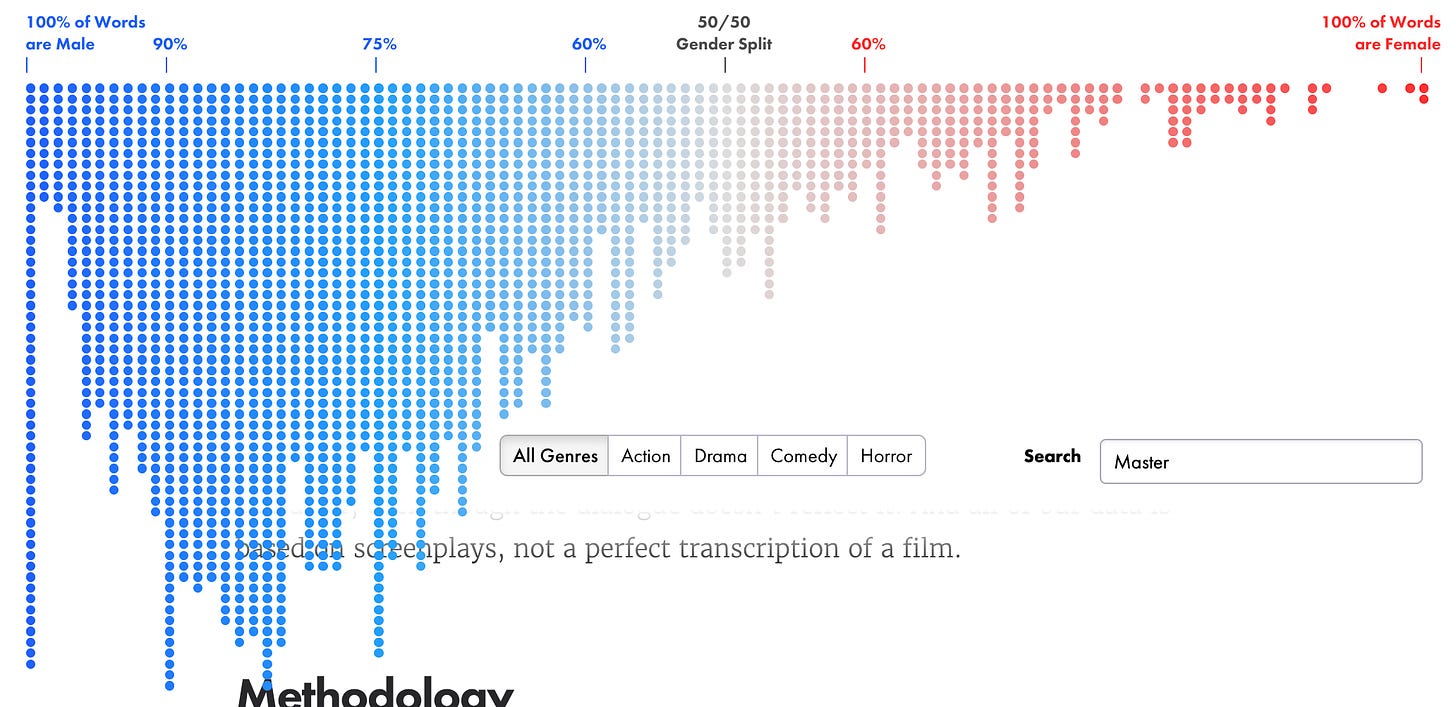

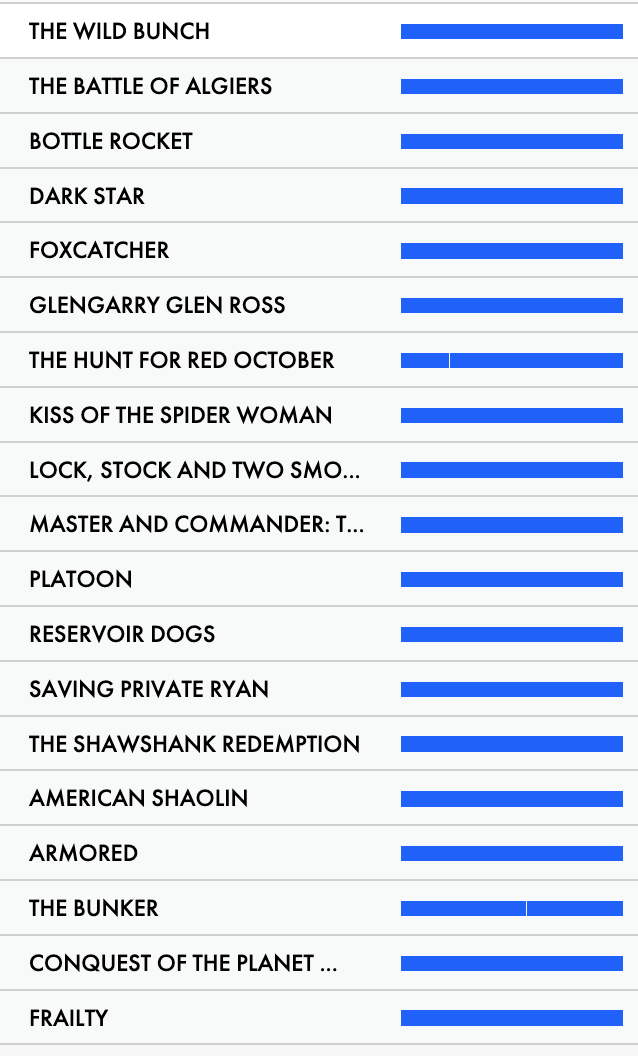

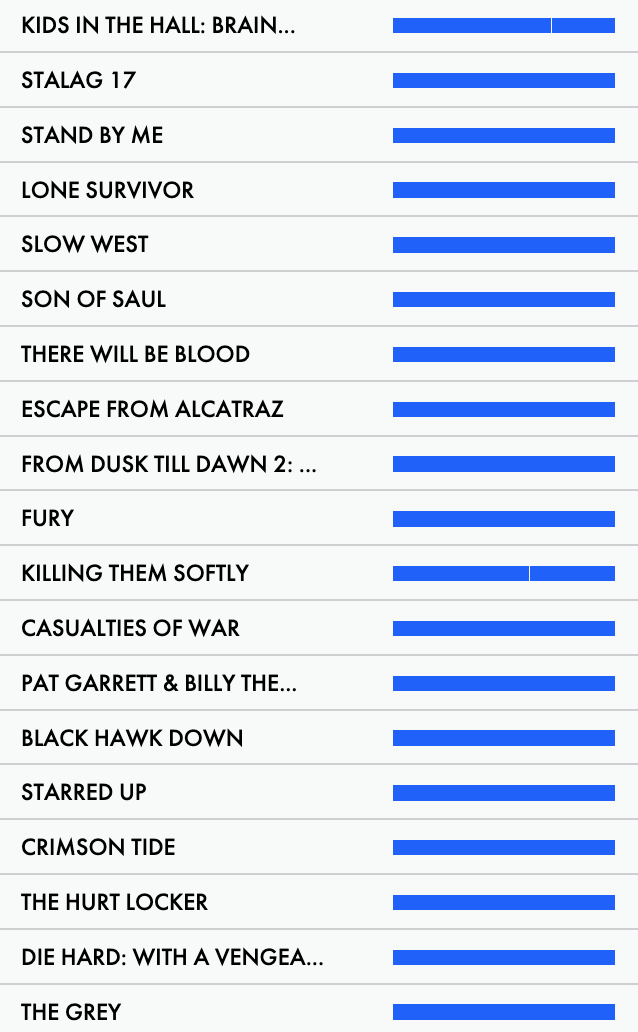

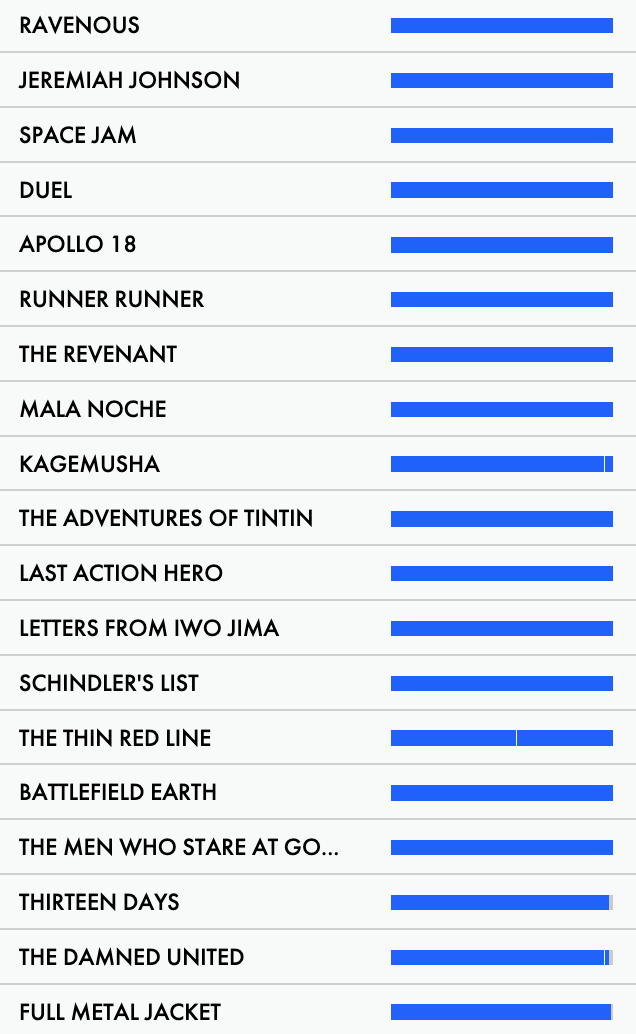

Something the article doesn’t mention is that movies in which virtually all the characters with at least 100 words of dialogue are male include a high proportion of classics:

I’ll put the rest behind the paywall.

To pick out one streak in this list: Master and Commander, Platoon, Reservoir Dogs, Saving Private Ryan, and The Shawshank Redemption would make a pretty good quintuple feature.

A lot of war movies, crime movies, prison movies, a gay prison movie (Kiss of the Spider Woman), and so forth.

What about all women movies? Back in the wonder year 1939, Clare Booth Luce’s play The Women was made into a superb comedy by director George Cukor. They tried remaking it in 2008, but it wasn’t very funny because the authoress’s satire on women was now considered sexist, so the new version pulled its punches. As I wrote in 2008:

The remake was intentionally declawed by its writer-director Diane English, creator of Candace Bergen’s Murphy Brown television show, out of feminist loyalty to the team. English complained, “… the movie had very old-fashioned ideas that were in great need of updating … The original play and film were written as a poison pen letter to shallow society women who would stab each other in the back over a man … I had to figure out a way to shift the focus. I wanted to celebrate women …”

Self-esteem boosting female empowerment plot developments ahoy! (Aren’t there any bitchy gay men left in Hollywood who could have done for the remake what Cukor did in 1939?)

So the 1939 version would be a classic with 100% female lines.

For some reason, the 2008 version of The Women isn’t in the database, so they only have 2 films that are all female and 7 more between 90% and 99% female in larger roles.

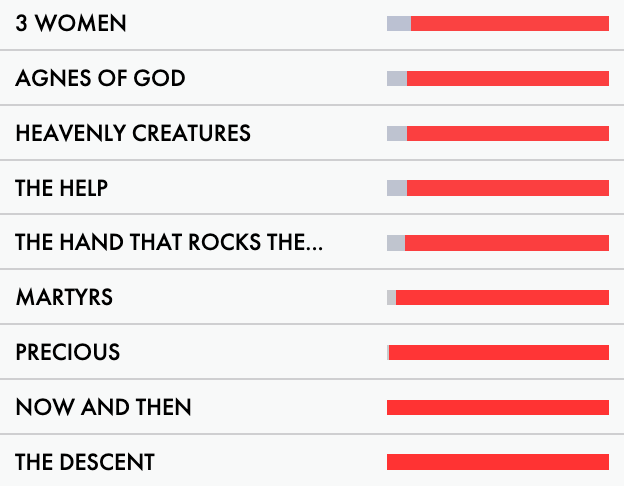

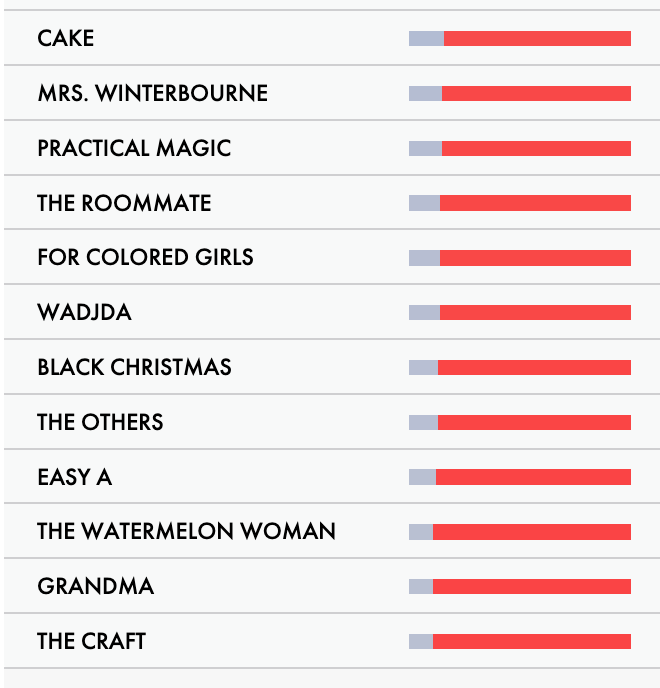

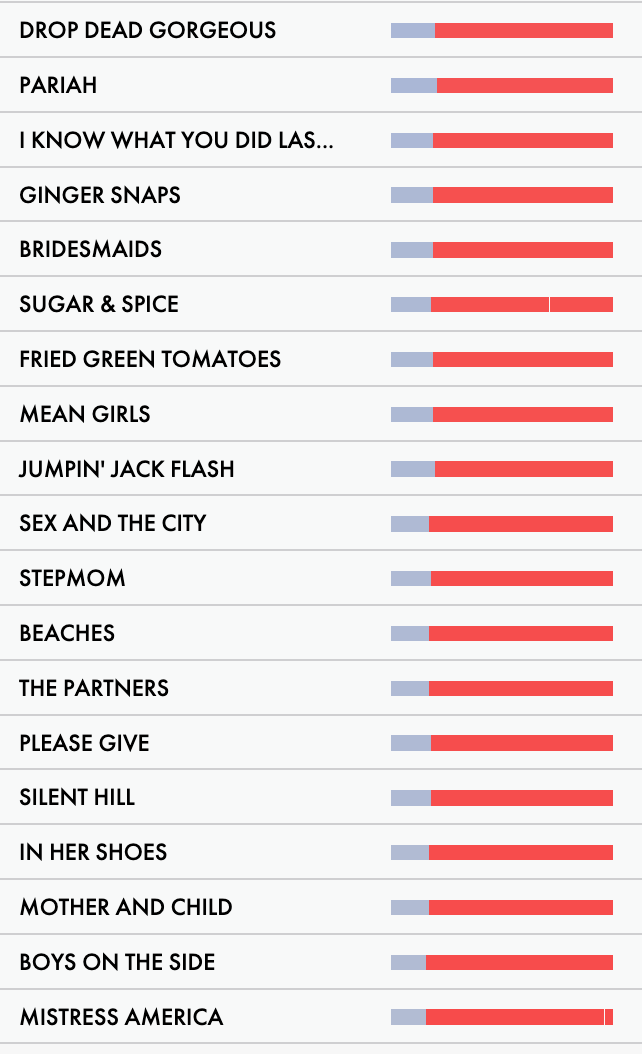

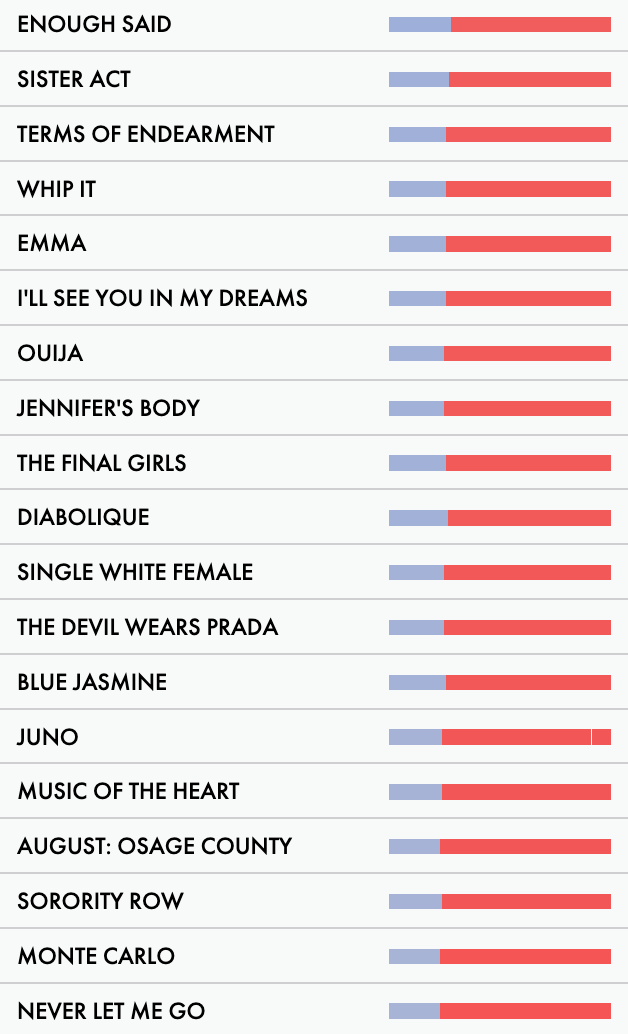

Next on the list:

There are some fine movies among these female dominated ones, but Still, the difference in quantity of very high quality movies between the two ends of the list is striking.

Some of that is likely bias due to their being more male critics and film aficionados. Men tend to be more nostalgic about public things like movies, so men put more effort into celebrating the best of the past, while women tend to be focused more on the next big thing in fashion. (Gay men tend to be the ones who are nostalgic about women’s movies.)

But it could also be that men make more great movies in part because they are focused more on the greats of the past and wish to compete with them.

A member of my family moved to Hollywood to be an actress. She landed a number of small parts in TV shows and some work as an extra in features, but could never make a living at it, so after a few years she went back to school and became an occupational therapist focusing on helping first time mothers adjust to the demands of their new role. She married a movie producer, whom she finds to be a fine husband and a great dad to their daughter. When they first got together, her friends all asked her if she would revive her acting career by appearing in his movies, to which she would reply, "Have you SEEN his movies?" She thinks it's wonderful he enjoys his work and is proud of his success, but that part of his life is strictly Guy Stuff as far as she is concerned, and she is very happy not being part of it.

Women are attracted to men based on what they say and do. Men are attracted to women based on how they look and...uh...

We go to movies, even action movies, (no homo) to fall in love.

One of my favorite re-watchable movies of (I was about to write 'recent years' then realized I'm old) is "Almost Famous". At its heart is the story of a woman desired by two very different men, yet most of the interesting dialogue and action is of and by the men.

I think this is even how the average woman prefers to take in the story. The one man demonstrates how he is a sexy cool cad of a rock star with far less substance than he thinks, while the other shows his less flashy talent and promising future while being too young and un-cool, more of a friend vibe who doesn't understand he has no chance with such a goddess .

The girl is quiet and mysterious (thus little dialogue)...not the most classically beautiful but somehow has a quality that drives men mad. That quality is never going to be witty dialogue