Wow, it turns out The Science shows SAT/ACT scores matter

A new study of elite colleges finds that high test scores predict freshman GPA better than high high school GPA.

There’s a new study out (although I wrote about the preprint over a year ago) using college admissions data from the putative top 12 undergraduate colleges (the 8 Ivies plus Stanford, MIT, Duke, and Chicago):

STANDARDIZED TEST SCORES AND ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE AT IVY-PLUS COLLEGES

John N. Friedman, Bruce Sacerdote, Douglas O. Staiger, Michele Tine

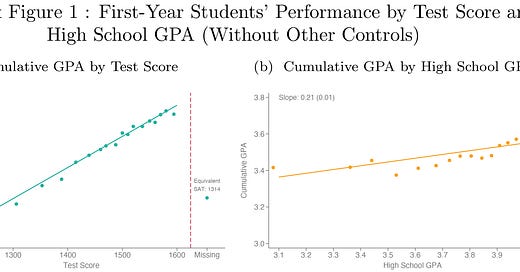

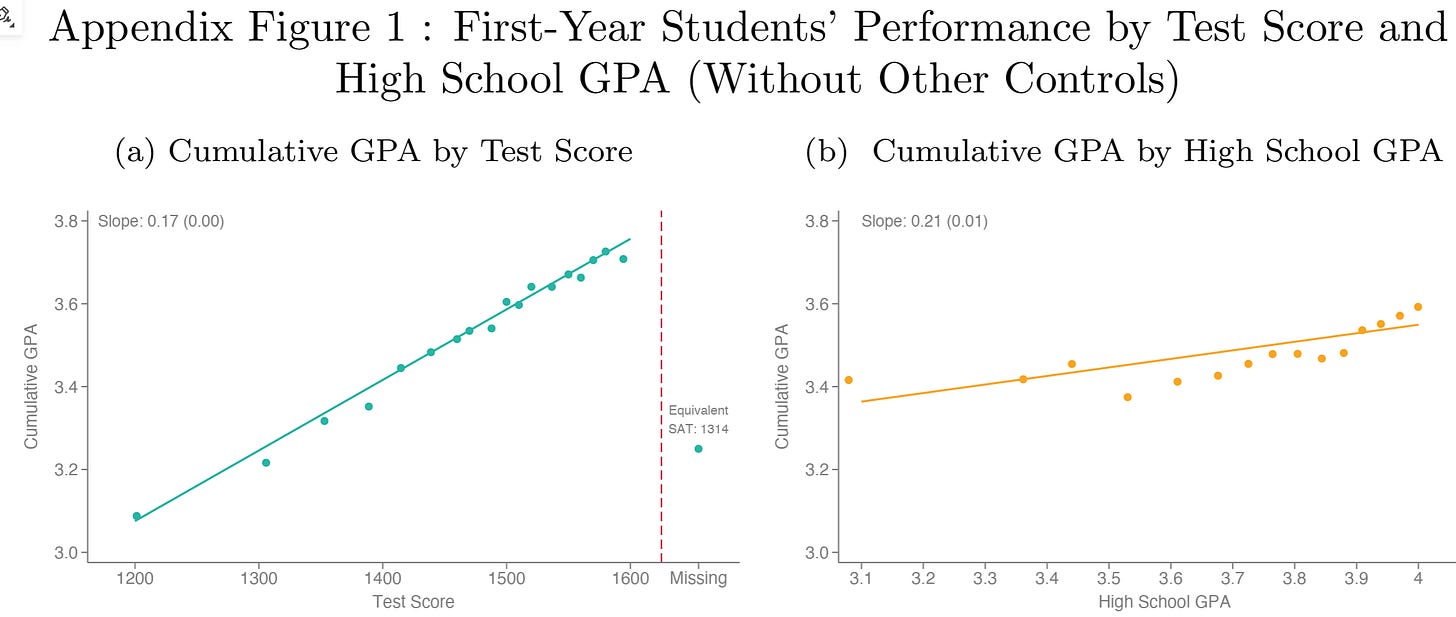

At the high end, college admission testing is much more predictive of freshman college grade point average than is high school grade point average:

Presumably, if the admissions committee knows that, to take local examples from my neighborhood, a 4.0 at academically demanding Harvard-Westlake is harder to achieve than a 4.0 at more artistic Oakwood (representative graduates: Lily-Rose Depp, Moon Zappa, and Wolfgang Van Halen, none of whose dads probably were a big help with their kids’ trigonometry homework, although Moon Unit Zappa’s grandpa seems likely to have been of use), then they can make better use of GPAs than in this study.

But how often do they know that?

But aren’t SAT scores just the result of rich parents paying for test prep? Surely, rich kids get their come-uppance in college when they are out-competed by striving poor kids?

Nah …

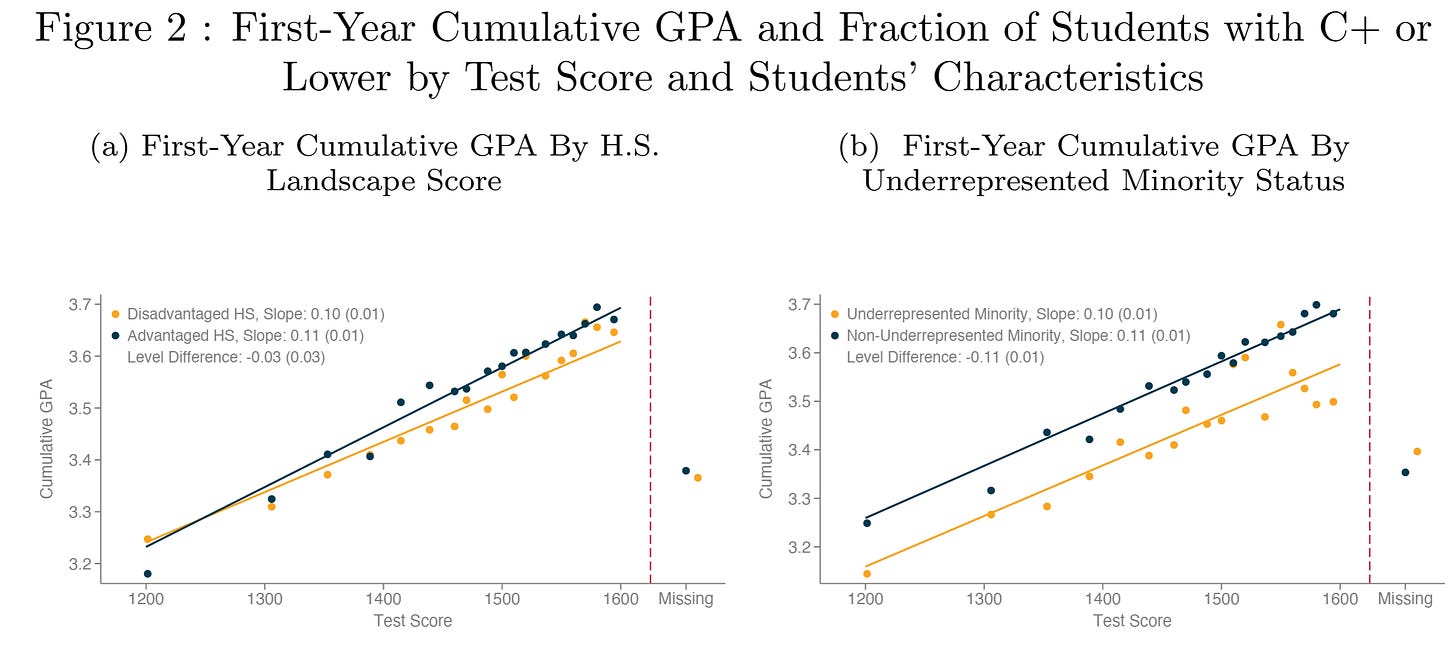

… if test scores are biased against a certain group of students, then those students will have a higher level of underlying academic preparation as compared to others with the same score, leading them to outperform academically once in college and judged in a system without such bias. Such might be the case if, for instance, students from advantaged backgrounds had more resources with which to prepare specifically for the SAT or ACT, inflating their test scores relative to others with the same underlying level of academic preparation but lacking these extra resources. Figure 2a shows a non-parametric representation of our test for bias between students attending more vs. less advantaged high schools. The relationship between test SAT/ACT scores and first-year college GPA is quite similar for all students, no matter the advantage of the high school they attended. Although not statistically distinguishable, the point estimates suggest that students from less advantaged high school slightly underperform their peers from more advantaged high schools with the same test scores. Figure 2b replicates this test for bias between URM and non-URM students; we similarly find that non-URM students slightly outperform URM students with the same SAT/ACT scores, though the relationship (while statistically significant) is not large. Figures 2c and 2d similarly replicate the test for calibration bias for our academic struggle outcome. Indeed, our results across different measures of student background and academic outcomes consistently show that test scores do not exhibit calibration bias against students from less advantaged backgrounds (see Appendix Table 1 and Appendix Figures 2 and 3).

In general, kids who go to better high schools tend to do better, not worse, than their SAT/ACT scores predict. This follows Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim rule: “There was no end to the ways in which nice things are nicer than nasty ones.”

One apparent pattern across these studies is that standardized test scores perform better in more selective college settings. Recent grade inflation could be eroding the information content of high school GPA most at the top, as more students are pushed up against the 4.0 cap. Goodman, Gurantz and Smith (2020) show that retaking SAT tests increases scores more for students lower in the test score distribution.

The rule for college admissions committees is only to look at the highest scoring test out of multiple attempts. Regression to the mean suggests that high scores from lower scoring groups are more likely to be flukes than high scores from high scoring groups.

Part of the problem is credential inflation: Both test scores and GPA are much more inflated these days. For example, in 1991, People magazine ran profiles of five of the 9 boys (no girls) in the U.S. who scored a perfect 1600 on the SAT. A few years ago I tracked down three of the five with perfect scores. One was a tenured professor of brain science at Georgetown, while one was a high school counselor whose motto was “What a long strange trip it’s been,” while the other had worked a number of high end corporate jobs but now mostly seemed to be into the art of motorcycle repair.

I’ve now found another 1991 perfect SAT scorer: Brian Naranjo, who is now a professor of physics at UCLA, and continues to publish prolifically on questions I will never ever understand.

At my pretty good private Catholic school, two of the 181 in the Class of ‘76 had perfect 4.0 GPAs. My vague recollection is that I was seventh out of 181 with a 3.81 GPA. These days with the 1.0 bonus just for taking Advance Placement classes, a GPA of 4.40 is common.

I think the SAT scoring algorithm has been adjusted over the years such that an 800 math score can be achieved despite failing to answer every question correctly. This probably doesn’t affect its’ predictive validity.

I also can “vaguely” recall my scores with three digit accuracy, as it was the lifetime apex of my brain’s capabilities. Soon afterwards I was introduced to the glories of beer.

"My vague recollection is that I was seventh out of 181 with a 3.81 GPA."

Ha ha, that's really "vague"... very cheeky Steve... :-)